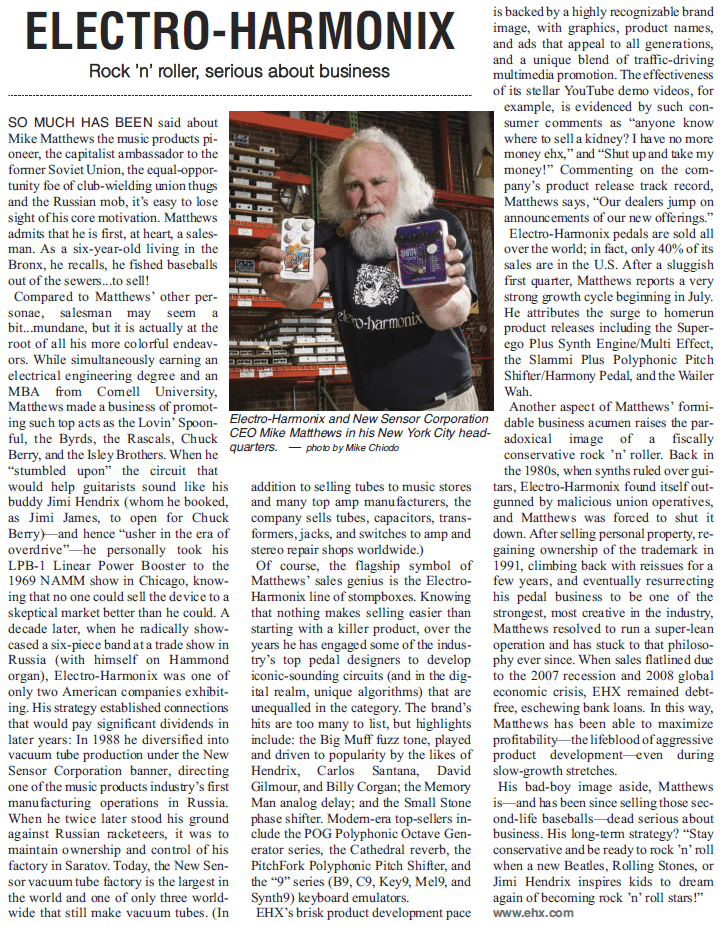

THE EHX STORY

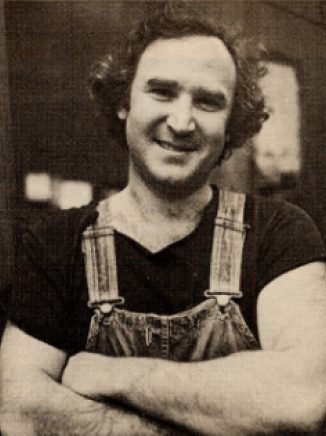

Mike Matthews,

Electro-Harmonix Founder & President

GENESIS

You can’t tell the story of Electro-Harmonix without sharing Mike Matthews’ life story, too. They’re intertwined and part of the same rich tapestry.

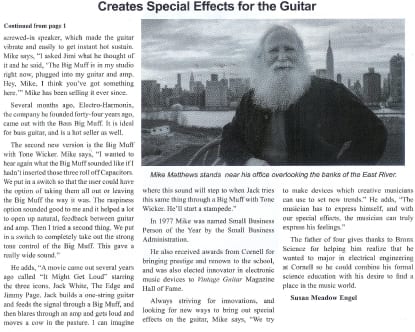

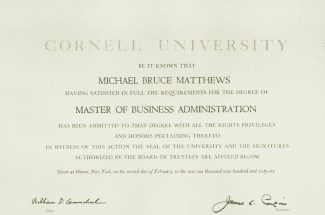

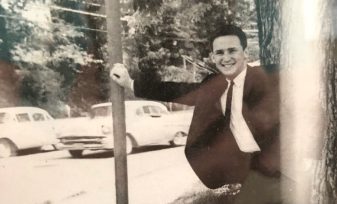

Mike Matthews, 1962 in his college apartment

1941

GROWING UP

1941

GROWING UP

As a child, Mike had a tenacious entrepreneurial spirit. In his own words, “Ever since I was five years old, I was into business. I always knew I wanted to start my own business. I grew up in The Bronx (NYC) in the 1940s. I used to fish balls out of the sewers with hangers and sell them. I bought a guy’s inventory who’d been making binoculars during World War II. It included all his prisms and lenses. I sold them in junior high school, creating a big fad with prisms. There were rainbows all over the school. Teachers didn’t know where they were coming from. When I went to camp and kids were playing golf, I’d be in the pond looking for golf balls to sell, and during rest period I’d sneak out and dive in the lake to retrieve snagged fishing lures to sell.

“As far as music is concerned, when I was very young my mother gave me piano lessons. I was five. I had a formal, classical teacher a year later. When I was seven, I started doing concerts at elementary school. In the fourth grade I was rambunctious and I climbed up the rafters in the classroom. To punish me, the teacher canceled my upcoming concert, so I got pissed off and quit playing. But in high school, when rock and roll was first evolving, I started getting involved in boogie-woogie on the piano and I got pretty good at it.

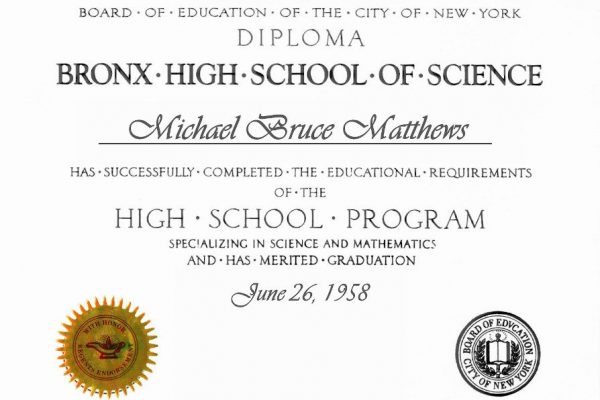

1958

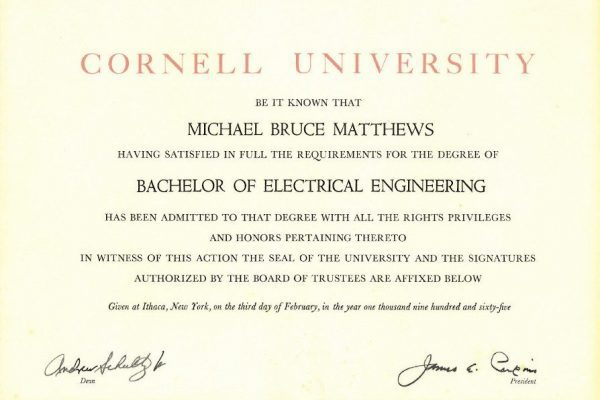

CORNELL DAYS

“At college at Cornell I saw my first live concert, an R&B band called the Sawyer Brothers. They had this incredibly soulful sound which really influenced me. I formed a band and played a Wurlitzer electric piano and Hammond M3 organ in the R&B style of the Sawyer Brothers. I really got into playing music and I was booking all our gigs. While in college at Cornell and in the summer on Long Island, I would also promote rock and roll bands. I hired The Coasters, The Isley Brothers, The Drifters, The Rascals, The Byrds, The Lovin’ Spoonful and many dozens more.

1966 – 1968

CORPORATE DAYS

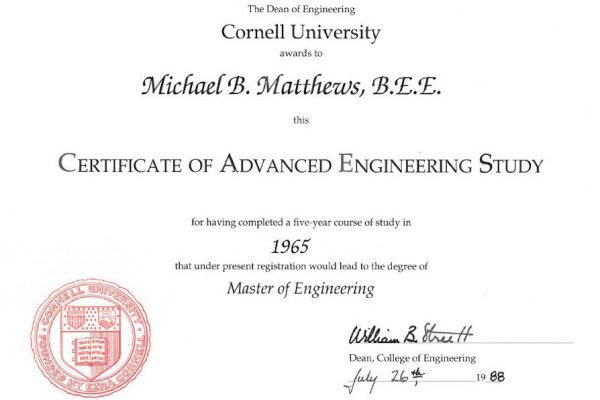

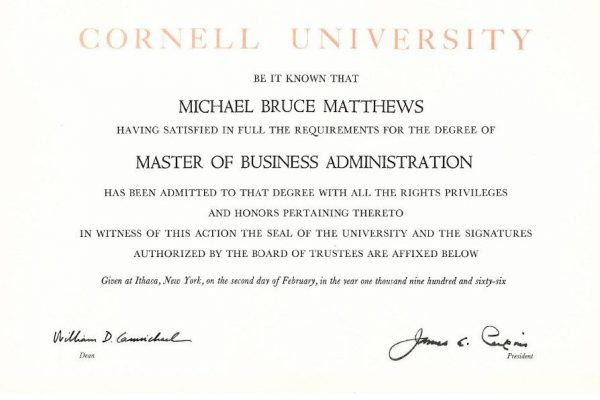

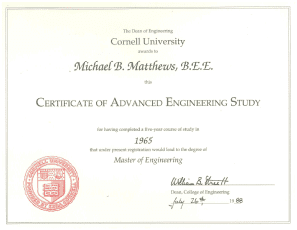

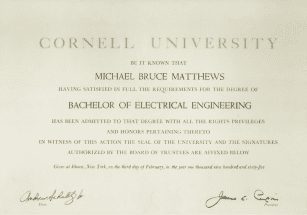

Mike graduated Cornell with undergraduate and master’s degrees in Electrical Engineering and an MBA in Business Management. He joined IBM as a computer salesman in 1965 but continued promoting concerts. One of those concerts included a young guitarist who would go on to superstardom.

1965 – 1970

HANGIN OUT WITH HENDRIX

Mike recalls, “I also became good friends with Jimmy James who eventually went back to using the name Jimi Hendrix. Here’s how it happened. During the summer of ’65 I booked Chuck Berry at the Highway Inn in Freeport, Long Island for $1000 a night for two nights and I had to get the backup band. The promoter who sold him to me called about a week before the gig and pleaded with me to hire this other band, Curtis Knight and the Squires. He said they had an amazing guitarist who played with his teeth. I didn’t want to make this investment because the people were coming to see Chuck Berry.

The agent was originally asking $600 for three nights and then said you can have them for $500 so I finally agreed figuring he’d owe me a favor. I had Chuck Berry go on first ‘cause I didn’t have any idea how the Curtis band sounded. I was in counting the money from the gig when, Steve Knapp, the guitar player for the band I’d put together to backup Berry came running in and said to me: ‘Hey, you’ve got to see this guy playing guitar!’ That was Jimmy James. He had a really fluid R&B style at the time and we hit it off.

I began hanging out with Jimmy James at his hotel room during my lunch breaks at IBM. He was living in a fleabag hotel in Times Square with no bathroom. There was just a bed and nothing else. We would just have band talks about this player, that player. One night, Curtis Knight and the Squires were playing at a club on the West Side and on break Jimmy was telling me how he wanted to quit and have his own band and be the headliner. I said, ‘If you do that, you’ll have to sing.’ He said, ‘I know. That’s the problem… I can’t sing!’ And I said, ‘Well, if you work on it, you can do it. Look at Mick Jagger, look at Bob Dylan, they don’t really sing, they just phrase stuff and they’re great.’ He said, ‘Yeah, you got a point.’ And I think my encouragement helped him to start singing. He had that same style of soulful phrasing. Later on, when he made it big as Jimi Hendrix and came back to New York City to record, he’d always invite me down to his recording sessions to hang out and dig the process.

I also became good friends with Jimmy James who eventually went back to using the name Jimi Hendrix.

Mike recalls, “I also became good friends with Jimmy James who eventually went back to using the name Jimi Hendrix. Here’s how it happened. During the summer of ’65 I booked Chuck Berry at the Highway Inn in Freeport, Long Island for $1000 a night for two nights and I had to get the backup band. The promoter who sold him to me called about a week before the gig and pleaded with me to hire this other band, Curtis Knight and the Squires. He said they had an amazing guitarist who played with his teeth. I didn’t want to make this investment because the people were coming to see Chuck Berry.

The agent was originally asking $600 for three nights and then said you can have them for $500 so I finally agreed figuring he’d owe me a favor. I had Chuck Berry go on first ‘cause I didn’t have any idea how the Curtis band sounded. I was in counting the money from the gig when, Steve Knapp, the guitar player for the band I’d put together to backup Berry came running in and said to me: ‘Hey, you’ve got to see this guy playing guitar!’ That was Jimmy James. He had a really fluid R&B style at the time and we hit it off.

I began hanging out with Jimmy James at his hotel room during my lunch breaks at IBM. He was living in a fleabag hotel in Times Square with no bathroom. There was just a bed and nothing else. We would just have band talks about this player, that player. One night, Curtis Knight and the Squires were playing at a club on the west side and on break Jimmy was telling me how he wanted to quit and have his own band and be the headliner. I said, ‘If you do that, you’ll have to sing.’ He said, ‘I know. That’s the problem… I can’t sing!’ And I said, ‘Well, if you work on it, you can do it. Look at Mick Jagger, look at Bob Dylan, they don’t really sing, they just phrase stuff and they’re great.’ He said, ‘Yeah, you got a point.’ And I think my encouragement helped him to start singing. He had that same style of soulful phrasing. Later on, when he made it big as Jimi Hendrix and came back to New York City to record, he’d always invite me down to his recording sessions to hang out and dig the process.

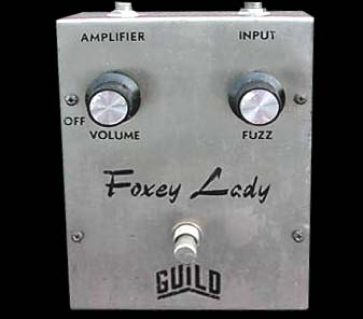

1967

FOXEY LADY PEDALS

While I was still at IBM, I had a growing urge to quit and go out and play with a band full time. In those days, “Satisfaction” with Keith Richards’ fuzz-tone guitar riff was the longest running No.1 hit of all time and Maestro couldn’t make their fuzz pedals fast enough. All the music stores in New York City were on West 48th Street and there was a repair guy there named Bill Berko who was making fuzz tones one at a time. He said, ‘Hey Mike, why don’t you come in with me? We can make these much faster.’ At that time I was married and my wife was kind of conservative. I wanted to make some quick money so I could say, ‘Here’s twenty-five grand, I’m going out playing, and you got a little security.’ I said, ‘OK.’ I figured I’d make enough so I could quit IBM and go out on the road. But it turns out he didn’t do any work, and I ended up doing that myself with a contractor in Long Island City. Al Dronge, the founder of Guild Guitars, wanted to buy them all so every couple of weeks I’d bring a few hundred pedals out to Guild in Hoboken, N.J. They would write me out a check, and I would go back to work at IBM. Al Dronge wanted to call them Foxey Lady pedals ‘cause Jimi was huge by then and everyone wanted to sound like him!”

BECOMING AN

ICON

Mike Matthews, 1970

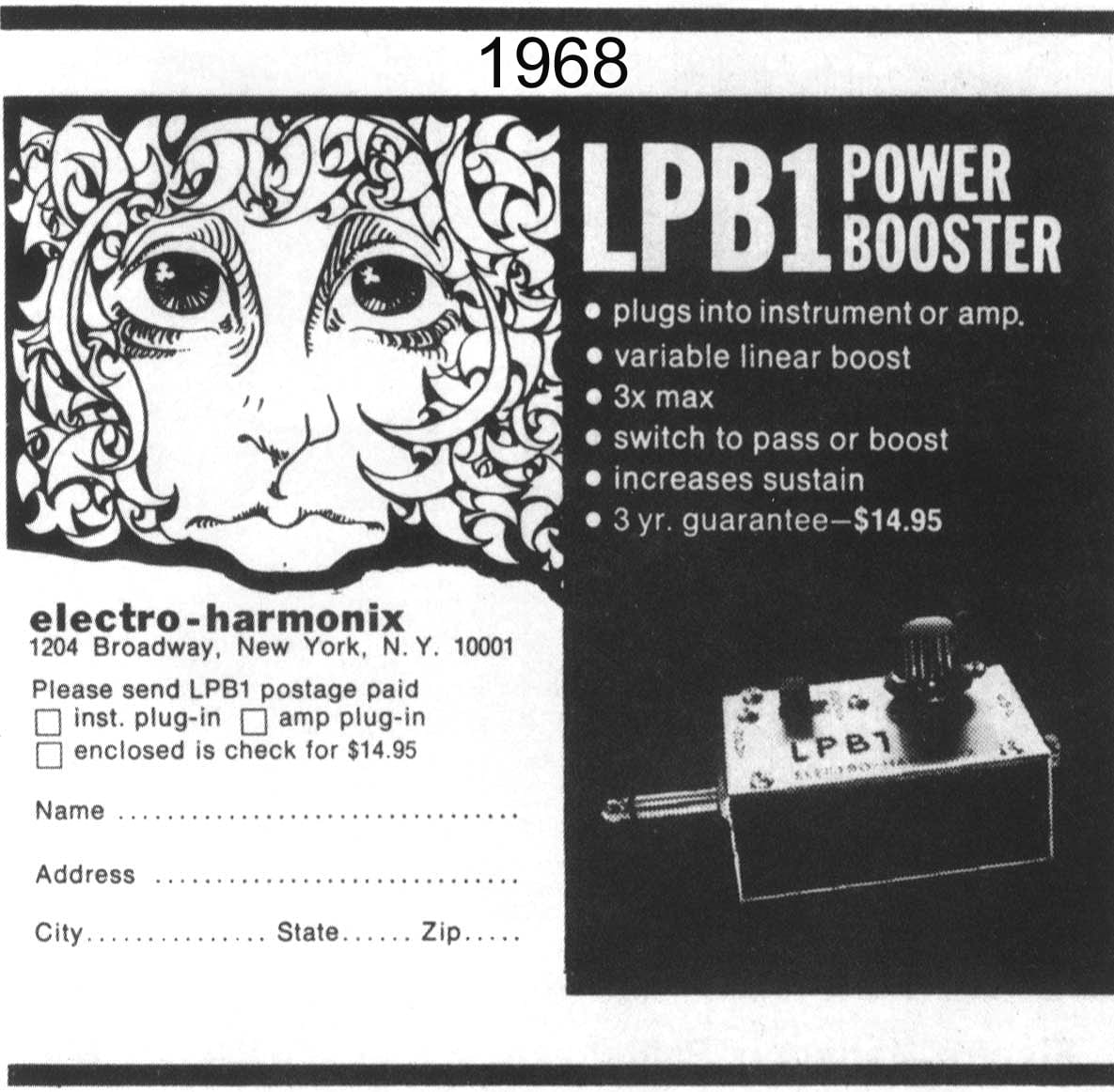

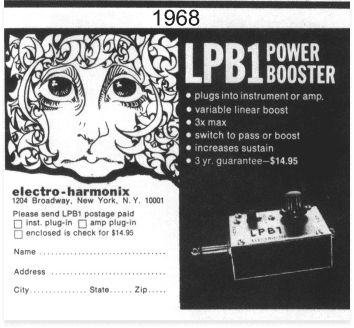

1968

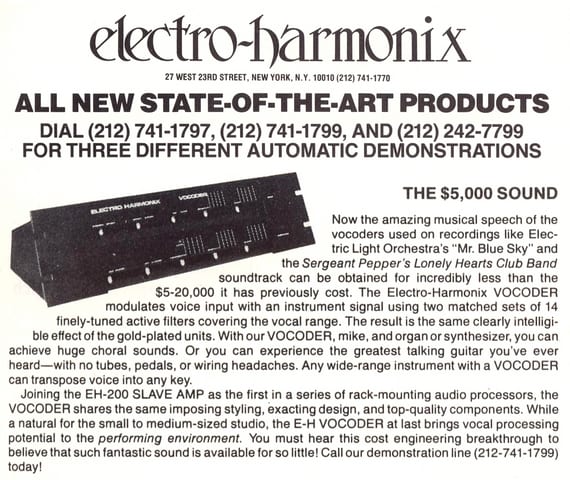

THE LPB-1 LINEAR POWER BOOSTER

Twenty-six-year-old Mike Matthews started Electro-Harmonix in 1968 with just $1000. That was when EHX’s first product, the LPB-1 Linear Power Booster, was born. It’s a device which helped usher in the Age of Overdrive, a phenomenon that profoundly affected the sound of modern music.

Mike describes it like this: “The first pedal that I built under Electro-Harmonix was in late 1968 and it was the LPB-1 Linear Power Booster. I hooked up with Bob Myer, an award-winning inventor from Bell Labs. I contracted with him to design a distortion-free sustainer and when I went to check out the prototype, I saw a little box plugged into the front of the sustainer prototype. I asked him, ‘What’s that?’ and he said, ‘Well, I didn’t realize that guitar put out such a low signal, so I just built a simple one-transistor booster to stick in the front.’ When I hit the switch, all of a sudden, the amp was so loud! I said, ‘Wow! That’s a product!’ In those days, amplifiers were designed with a lot of headroom. There was no such thing as overdrive. So, you would turn them up to 10 and they would still be clean and loud. But with this device, you could make the amp much louder, but then overdrive it. I called it the Linear Power Booster, or the LPB-1, and started selling them mail order and then in stores. We still sell tons of LPB-1s today.

1969

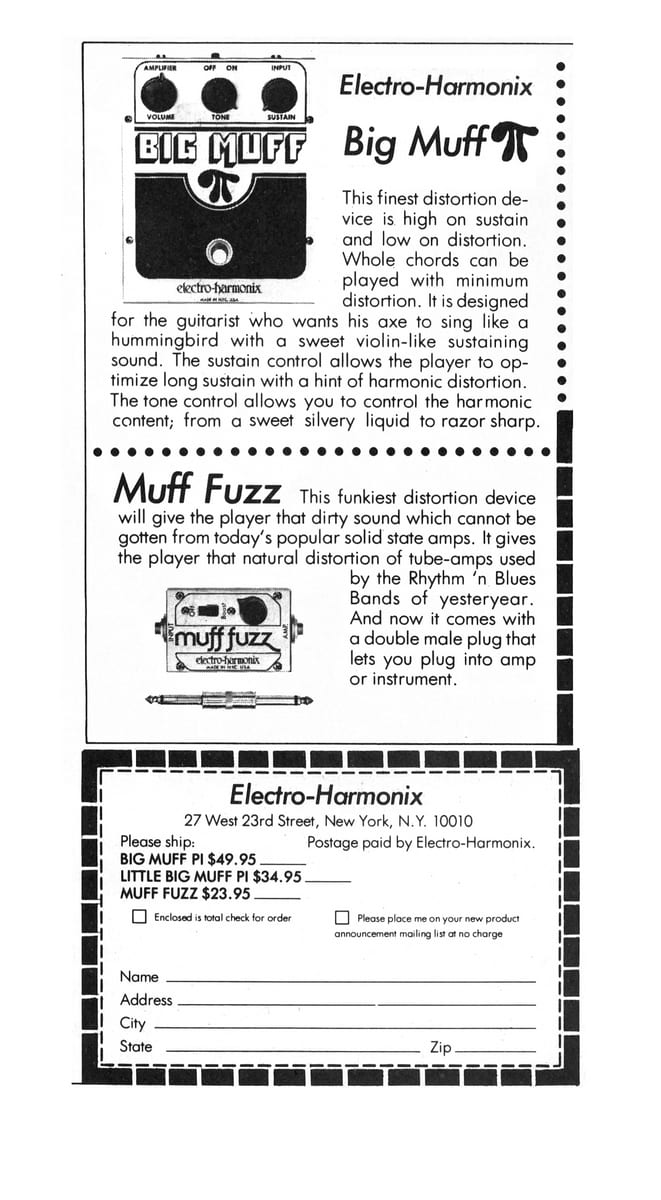

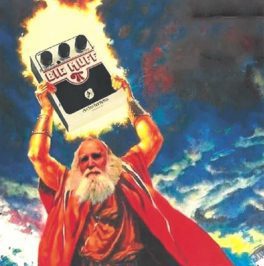

BIG MUFF PI

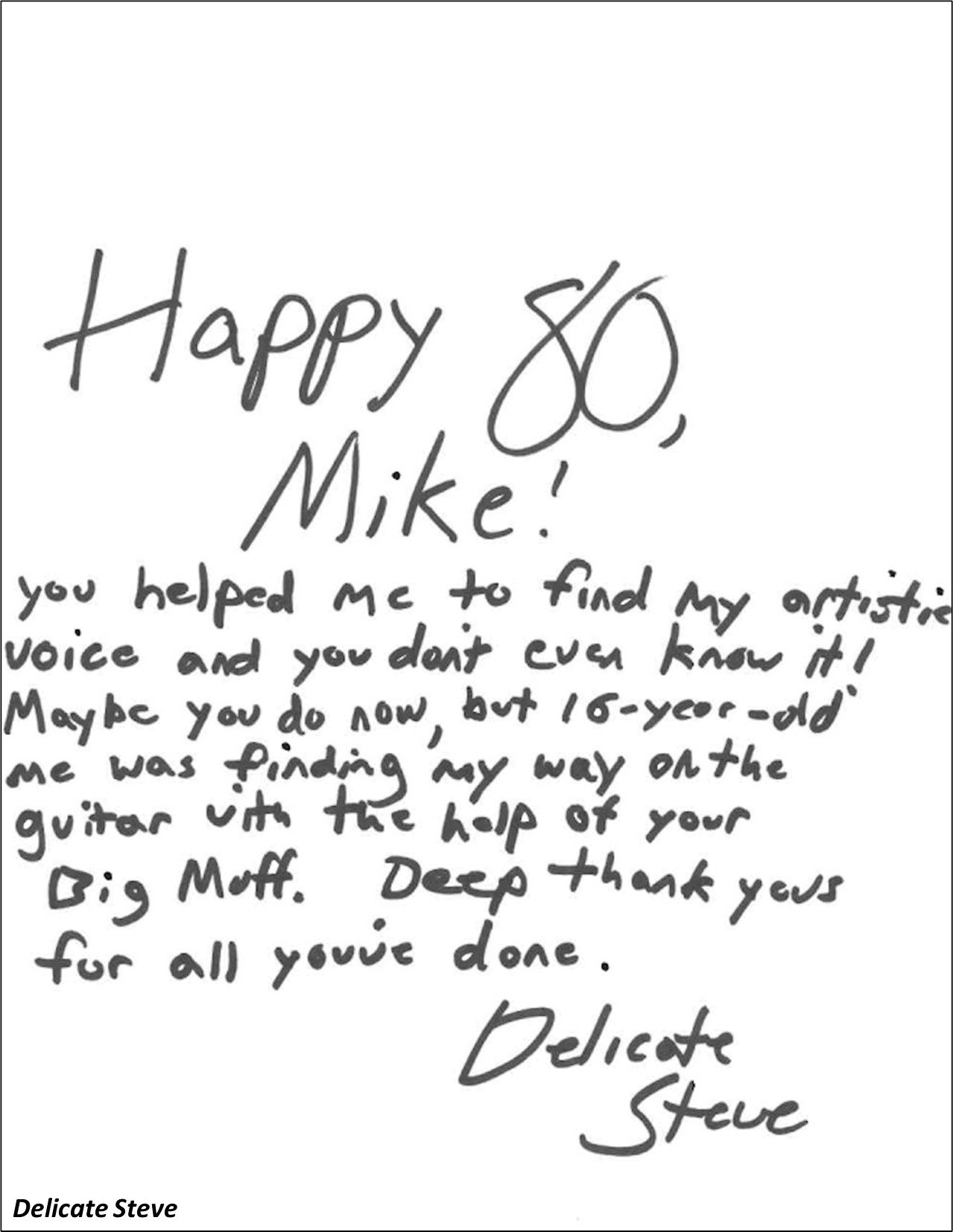

Just one year later, in 1969, Mike introduced the Big Muff Pi. It’s the pedal Electro-Harmonix is probably best known for — a game-changer with a roster of users that reads like a who’s who of popular music. Prominent Big Muff players include Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour, Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins, The Isley Brothers’ Ernie Isley, Carlos Santana, J Mascis of Dinosaur Jr., Jack White of the White Stripes and many more. Mike relates, “We plunged into production and I brought the very first units up to Henry (Henry Goldrich, the son of Manny’s founder, Manny Goldrich), the boss at Manny’s Music on West 48th Street in New York City. About a week later, I stopped at Manny’s to buy some cables and Henry yelled out to me, ‘Hey, Mike, I sold one of those new Big Muffs to Jimi Hendrix!’ Shortly thereafter at one of Jimi’s recording sessions I saw the Big Muff on the floor and plugged into his amp.

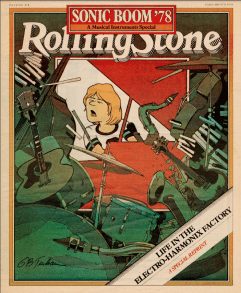

1978

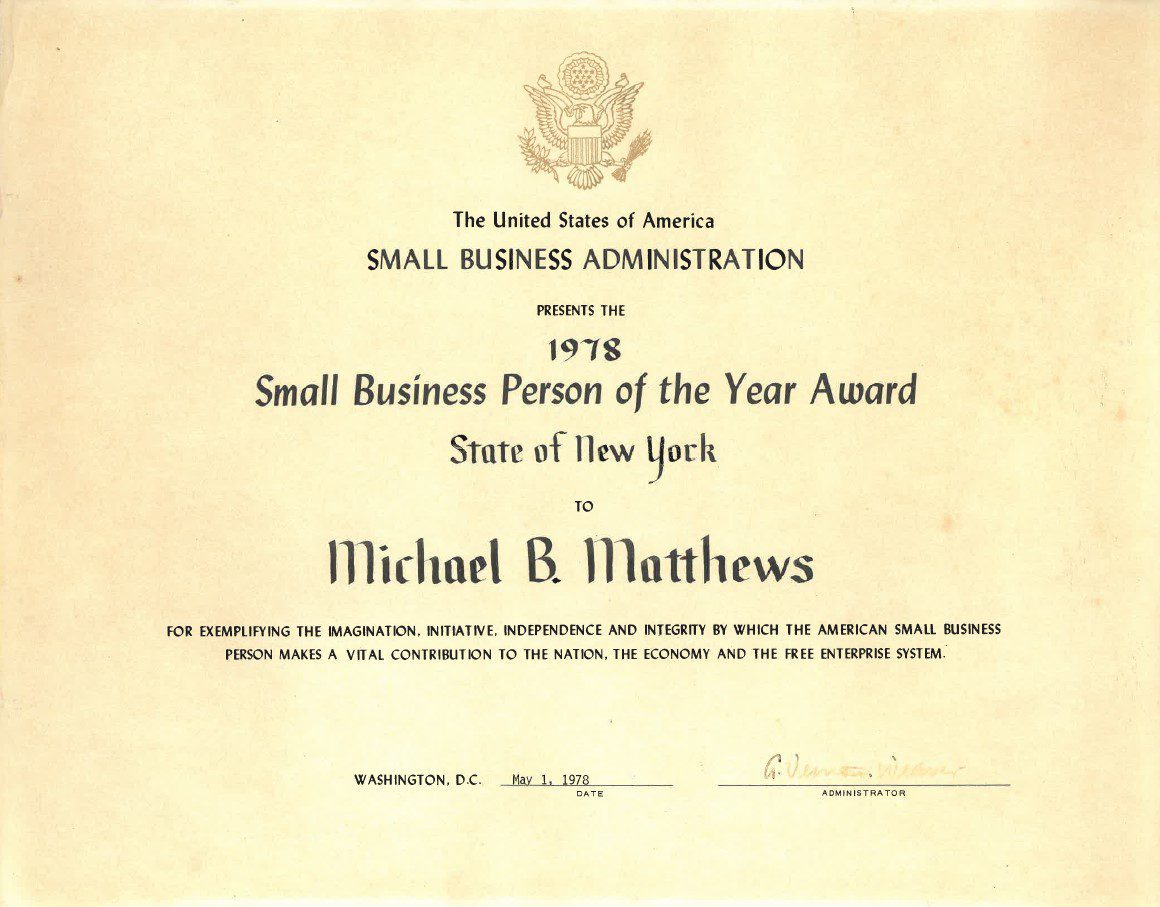

NY BUSINESS PERSON OF THE YEAR

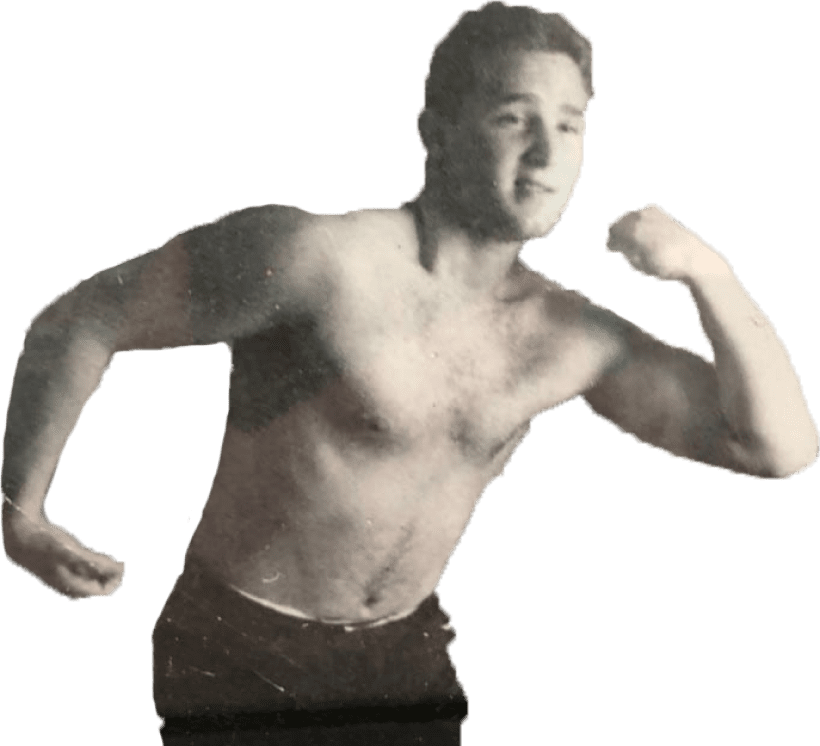

Mike Matthews, 1978 New York State Small Business Person of the Year

1978

NY BUSINESS PERSON OF THE YEAR

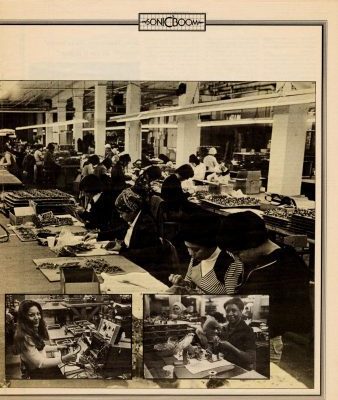

In 1968, first year sales for EHX amounted to $50,000. By ten years later they’d reached $5 million and the company employed over 250 people from many diverse backgrounds. Most began as unskilled workers and Mike gave unlimited opportunities for advancement. EHX’s VP of Sales was an African American fellow named Willie Magee; he’d played guitar on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Manny Zapata, the Director of Foreign Marketing, was an immigrant from Colombia. Both had started out with the company as unskilled laborers and worked their way up. Mike’s philosophy was that workers could advance based on merit, rather than seniority. In 1978 Electro-Harmonix was flying high and Mike Matthews was named New York State’s Small Business Person of the Year.

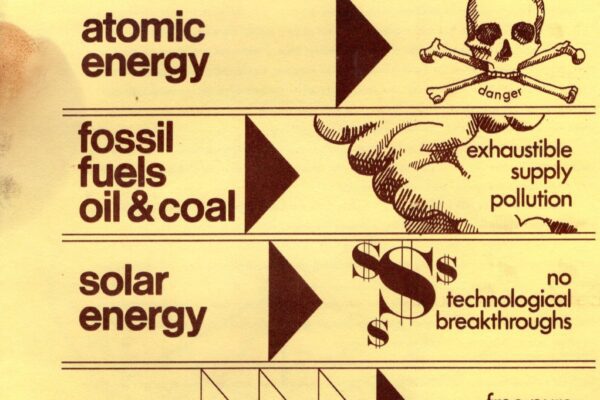

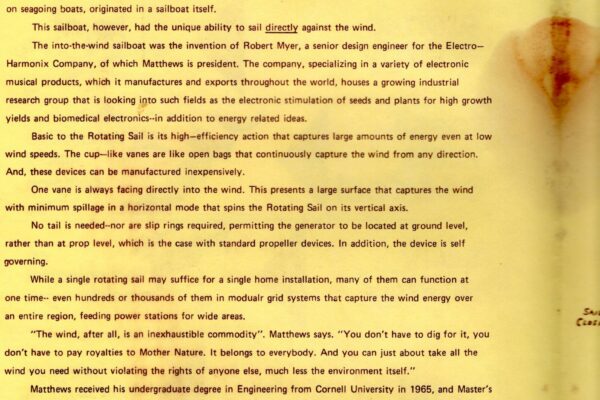

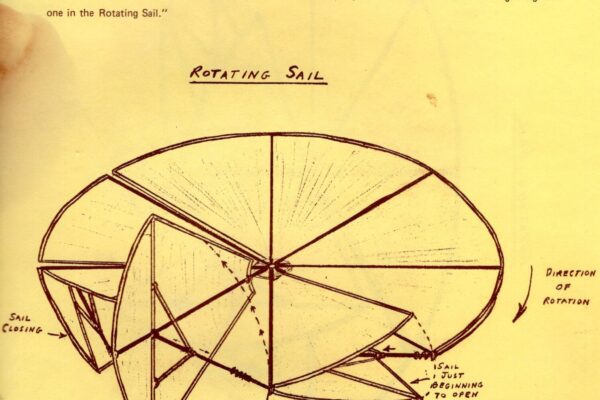

The Answer is Blowin’ in the Wind

Rotating Sail Electric Generator Proposal

Far out concepts have always been a hallmark of Mike Matthews and Electro-Harmonix.

LATE 70s

HALL OF SCIENCE

It was during this period, the late ‘70s, that Mike would do two things that show how unconventional, how “outside the box”, his approach to business is. The first was opening the Electro-Harmonix Hall of Science at 150 West 48th Street in New York City. At the time, West 48th Street was Music Row, the absolute epicenter for music gear. The block was filled with music stores… one next to the other that lined both sides of the street. Every musician that passed through New York City made a pilgrimage to West 48th Street and at any given moment it would not be unusual to see anyone from Stevie Wonder to Buddy Rich making the rounds. It was in the middle of all this that Mike opened the EH Hall of Science, a product and brand exhibition center complete with a stage where Electro-Harmonix product experts demonstrated, self-demo kiosks where musicians could try products and a cool, open, inviting vibe where musicians, musician wannabees and tourists could groove on all things Electro-Harmonix. One of the most striking aspects of the Hall of Science was its dazzling array of innovative electronic art displays. While direct sales were not part of the package, it was easy for interested parties to simply walk out the door to buy at their favorite music store down the street.

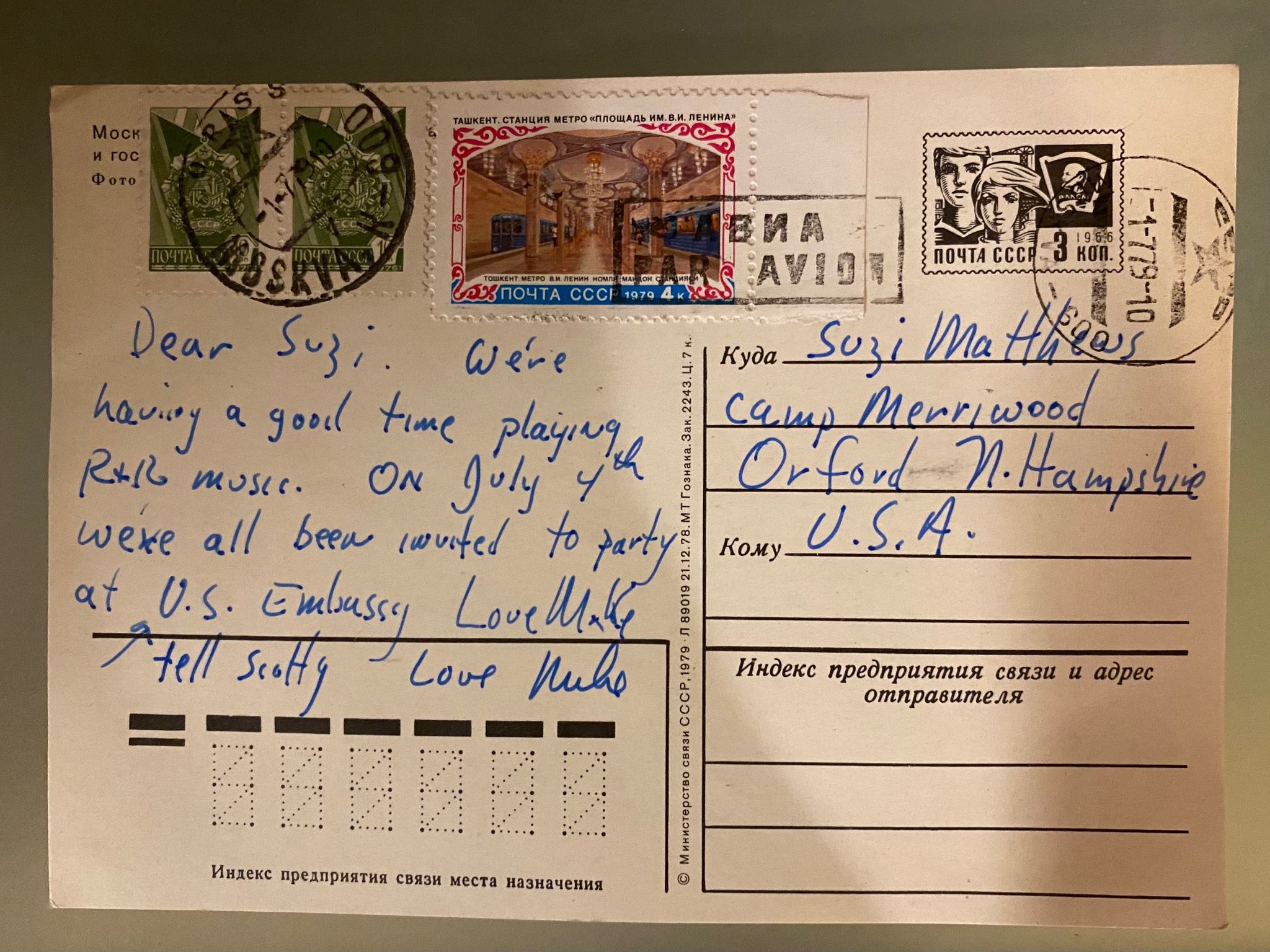

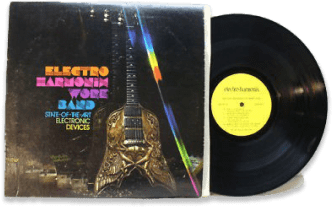

1979

MOSCOW CONSUMER EXPO

The second was taking the Electro-Harmonix Work Band, a group of five other musicians and himself, to perform in Russia over a ten-day period. In 1979 the U.S.S.R. Chamber of Commerce and Industry opened its Consumer Goods Exhibition in Moscow to international participants for the first time. The event took place in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park and Electro-Harmonix was one of only two exhibitors from the U.S.A.— the other was Levi Strauss. Several dozen exhibitors from Japan and Germany shared the same pavilion. The Work Band, totally equipped with the latest EHX pedals, played to packed crowds and rocked the appreciative audience who couldn’t get enough of the band’s brand of rock and roll.

The Work Band went on three times a day and whenever they did it could be heard throughout Sokolniki Park. People would hear it and they’d leave the other exhibits and pavilions in droves to catch the show. It was a celebration of American culture and music with Electro-Harmonix at the fore, and the seeds sowed on that trip would bear incredible fruit for Mike and Electro-Harmonix in years to come. More about that later.

DEATH

OF A

DREAM

Mike Matthews,

with Electro Harmonix Mini-Synthesizer

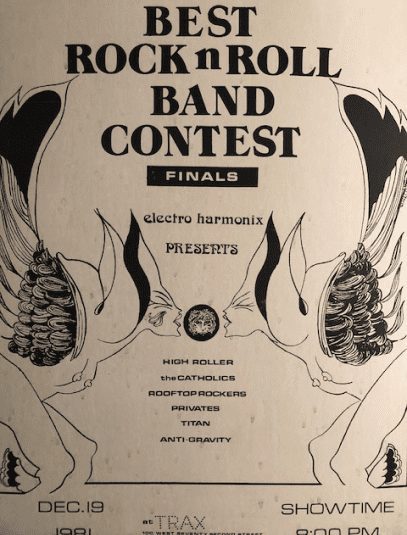

1981

THE UNION TARGETS EHX

Success doesn’t always come easy and in 1981 Electro-Harmonix attracted the attention of the Plastic, Moulders’ and Novelty Worker’s Union, Local 132, a branch of the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union. They offered Mike a “sweet-heart deal” to make Electro-Harmonix a union shop in which all workers would have to join Local 132. ‘It won’t cost you a dime. In fact, you can save money,’ he was told, but Mike rejected their overtures.

On the morning of Monday, August 10, 1981, a raucous crowd of outside agitators assembled in front of Electro-Harmonix. As Mike approached the building’s entrance he was accosted by several toughs. His adrenaline kicked in and he managed to hold them off, but an employee named Erasmo who jumped to his aid had his front teeth knocked out. As employees emerged from the subways they were confronted and asked to sign union cards. When they refused, they were pelted with eggs, and threatened with fists and clubs. Workers trying to enter the building had to run a gauntlet of kicking, punching and screaming outside thugs the union had hired.

When you get hit with a hurled egg, it doesn’t just splatter. It hurts!

-Mike Matthews

Success doesn’t always come easy and in 1981 Electro-Harmonix attracted the attention of the Plastic, Moulders’ and Novelty Worker’s Union, Local 132, a branch of the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union. They offered Mike a “sweet-heart deal” to make Electro-Harmonix a union shop in which all workers would have to join Local 132. ‘It won’t cost you a dime. In fact, you can save money,’ he was told, but Mike rejected their overtures.

On the morning of Monday, August 10, 1981, a raucous crowd of outside agitators assembled in front of Electro-Harmonix. As Mike approached the building’s entrance he was accosted by several toughs. His adrenaline kicked in and he managed to hold them off, but an employee named Erasmo who jumped to his aid had his front teeth knocked out. As employees emerged from the subways they were confronted and asked to sign union cards. When they refused, they were pelted with eggs, and threatened with fists and clubs. Workers trying to enter the building had to run a gauntlet of kicking, punching and screaming outside thugs the union had hired.

Mike Calls Out Unions on NBC

Late that Monday morning, Mike reached out to NBC news reporter, Jim Van Sickle, who he knew from a story the reporter had done about Electro-Harmonix several months earlier. Mike told him what was happening and, as he says, “Jim told me it sounded newsworthy, but he only reported the news… the stories that ran were decided by the desk editor. I’ll relay your comments to him.” On Wednesday afternoon Mike received a call from Van Sickle who told him that NBC had hidden crews at the nearby Flatiron Building and in unmarked vans, and that they’d filmed the organizer’s strong-arm tactics. Mike explains, “This ongoing story was aired on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday on Channel 4 News and I was invited to appear on Friday’s NBC Live At 5 television show where I castigated labor racketeering across the country!”

Chango went berserk…throwing punches. They scattered and that was the last time any of them had anthing to say to Chango!

CHANGO QUIETS THE PICKETERS

Chango went beserk…throwing punches. They scattered and that was the last time any of them had anthing to say to Chango!

During the picketing, United Parcel Service, the NYC police and others refused to cross the “picket line.” One interesting anecdote involves Mike and a friend named Charles Everett whose nickname was Chango. Chango was an African American, a street savvy Brooklyn native, and a popular drummer around New York City who Mike had hired to help out temporarily. Here’s how Mike tells it, “I rented a truck to take packed orders to the central UPS facility in Manhattan and Chango came along riding shotgun. When we arrived back at Electro-Harmonix headquarters on West 23rd Street I stopped to let Chango off before parking the truck. All of a sudden, several of the union goons yelled out at Chango, ‘Hey N-word!’ Chango went berserk, ran out of the truck and flew into these thugs throwing punches. They scattered and that was the last time any of them had anything to say to Chango!” Mike and Chango remained friends until the drummer’s passing in late 2018 and at company parties Mike would often hire Chango and his band to perform.

The Dream Dies

Mike was factoring the company’s accounts receivables through the Philadelphia National Bank and Electro-Harmonix’s financial problems grew, accelerated by the thug’s disruptive tactics. Then, convinced that the company couldn’t survive, the bank immediately halted its financing, crippling the company’s cash flow. It was a savage blow.

Electricity was cut off and Mike brought a gas generator in to provide limited electric power. He and his work force maintained high morale in the face of these hardships, but recalls, “We fought for our rights but could not overcome the financial setbacks and afterwards were forced to liquidate.” Mike had to close down the factory and file for bankruptcy.”

Ultimately, the National Labor Relations Board ordered the union to “cease and desist.” Unfortunately, it was too little, too late.

RISING

FROM THE

ASHES

Mike Matthews,

with Sovtek Guitar Amp

EARLY 90s

FILLING THE VOID

Mike’s trip to the U.S.S.R. with the Work Band sowed the seeds by which he was able to rebuild Electro-Harmonix and grow it back into a thriving business. He realized that the Russians couldn’t buy products from him—they didn’t have hard currency—but they were very eager for U.S. dollars. With his finely tuned entrepreneurial instincts, he thought about what he could buy from Russia. Mike recalls, “I got the idea to buy cheap integrated circuits which we called jellybean ICs from Russia. At Electro-Harmonix I’d seen these cycles every three years or so where, when manufacturers came out with a new series of integrated series that were hot, they’d stop making these cheap jellybean fill-ins and they’d end up costing a lot or you couldn’t get them. So, I figured if the Russian quality was good, when these cycles hit, I could fill a void and make a bundle! So, I started developing that business.

1998

MIKE BUYS A VACUUM TUBE FACTORY

“In those days everything was centrally controlled and one day, in 1988, when I went over to the Ministry of Electronics, I saw vacuum tubes hanging on the wall. I thought to myself, ‘Vacuum tubes? Those are used in guitar amps!’ So, I said ‘Let me get some samples of these’ and they sent them over to me in wooden boxes. I took them out to Long Island to my friend Jesse Oliver who’d designed most of the early Ampeg amps and asked him to check them out. He said, ‘Mike, these tubes are good’ so I switched from the ICs into the vacuum tubes. I was working alone, out of my apartment, and the tubes would be up to the ceiling. I was doing it all by myself. People in the industry knew me. I’d call up the service shops around the country and orders built. It grew to where I was the first American invited to the city where the biggest vacuum tube factory in the world was, it was part of a military factory, and now, we own 100% of the factory!” Mike bought the factory, in Saratov’s Reflektor industrial complex, in 1998 and grew it into arguably the largest vacuum-tube supplier in the world with a customer list that included guitar-amp makers Marshall, Fender, Vox and Peavey, as well as audiophile manufacturers such as McIntosh and Audio Research.

Looking back, he says, “Russia collapsed in the early ‘90s and the factory that made these tubes was a conglomerate, they made integrated circuits, clocks, optical devices… and they broke up their factory into several parts, and I was continuing to sell the tubes. But they borrowed a lot of money from a Russian bank, and they couldn’t repay it, and they came to me, and said, ‘We’ve got to either close or sell the company to you or Groove Tubes. At that time, selling vacuum tubes was by far the biggest part of my business, so I bought the factory!”

LATE 90s

BACK IN BUSINESS

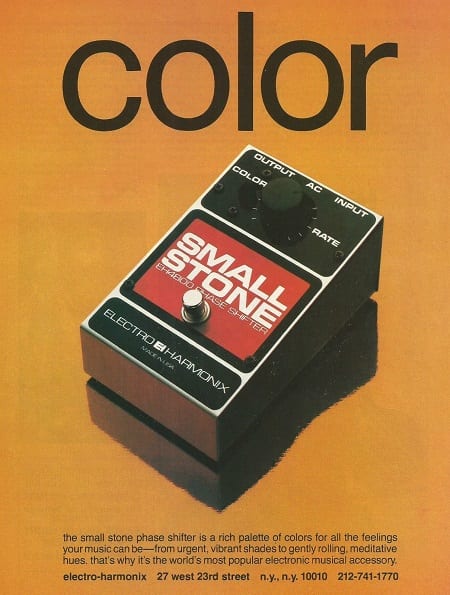

Later, Mike observed that there was a flourishing market for vintage music gear. He says, “In the early ‘90s I noticed that all the Electro-Harmonix pedals that I was making in the ‘70s were selling at big markups. In the ‘70s there was nothing called the vintage market, the vintage market developed. So, I started making Electro-Harmonix pedals again. I gave the circuit diagram for the Big Muff and a sample to a small military factory in St. Petersburg that was desperate for work. They laid out the pc board, designed a new housing, and they made them for me. Later on, I expanded and added the Bass Balls and Small Stone phaser. Then I started reissuing all the popular Electro-Harmonix pedals and making them in New York City. Eventually, I put together an expanding development team to design totally new pedals.

Later, Mike observed that there was a flourishing market for vintage music gear. He says, “In the early ‘90s I noticed that all the Electro-Harmonix pedals that I was making in the ‘70s were selling at big markups. In the ‘70s there was nothing called the vintage market, the vintage market developed. So, I started making Electro-Harmonix pedals again. I gave the circuit diagram for the Big Muff and a sample to a small military factory in St. Petersburg that was desperate for work. They laid out the pc board, designed a new housing, and they made them for me. Later on, I expanded and added the Bass Balls and Small Stone phaser. Then I started reissuing all the popular Electro-Harmonix pedals and making them in New York City. Eventually, I put together an expanding development team to design totally new pedals.

FROM

RUSSIA

WITH

DREAD

FROM RUSSIA

WITH

DREAD

Mike Matthews,

with Electro-Harmonix vacuum tube

SUCCESS IN RUSSIA

As the ‘90s gave way to the new millennium, Electro-Harmonix continued to flourish. Classic products were reissued and totally new pedals were brought to market as the company’s product line grew. By 2005 the Electro-Harmonix pedal line had grown to over 40 SKUs. Nevertheless, vacuum tubes imported from Russia continued to be the main part of EHX’s product mix, and the company’s portfolio featured fabulous vacuum tube brands: Electro-Harmonix, EH Gold, Genalex, Mullard, Sovtek, Svetlana and Tung-Sol.

In 2005 Mike’s Russian tube factory employed over 800 skilled workers and sold about 170,000 tubes a month. Production had grown some 300% since he bought the ExpoPul factory in Saratov in 1998, making it the largest producer of vacuum tubes in the world.

2005

TROUBLE IN RUSSIA

At that time in Russia, corporate raiders who engaged in nefarious practices were taking over businesses right and left, and white-collar corruption backed by racketeer muscle was rampant. RBE (Russian Business Estate), a company headquartered in Samara, began raiding Saratov-based companies. As Mike tells it, “The Reflektor complex housed a huge electronics conglomerate that made optical products, clocks, integrated circuits, vacuum tubes and a lot more. Our vacuum tube factory was the largest part of it. RBE bought up the rest of the Reflektor complex including the utility company, RefEnergo, that provided power for the entire compound. They wanted to buy ExpoPul and made me an offer of $400,000. The factory had cost me more than that in 1998 and now had a turnover of $600,000 or so a month, but I had no intention of selling, anyway! RBE approached the director of the factory, Vladimir Chinchikov, and told him, ‘Matthews better sell. If he doesn’t, we’re going to make big trouble for you!’”

“RefEnergo was now a subsidiary of RBE and they sent us a letter saying our factory’s electricity would be disconnected on January 1, 2006.” As Mike describes it. “There are two kinds of energy that RefEnergo provided, primary, which is electricity, and secondary which are gasses like hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, etc. They made a mistake, though, because by law they were not allowed to shut off our electric power. Then they backtracked and said they really meant our secondary energy would be turned off because of the need for refurbishment, but they screwed up again because they hadn’t notified other secondary energy users that they’d also be cut off!”

CNBC NEWS SPECIAL REPORT

2006

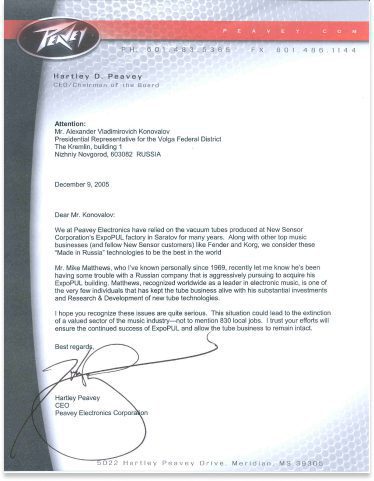

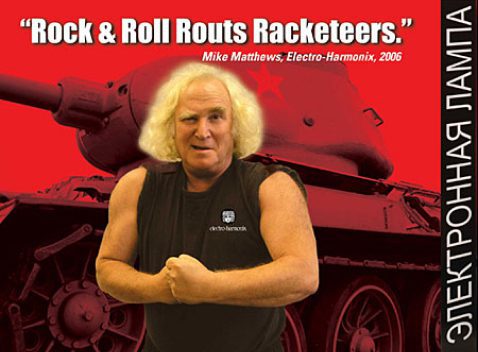

ROCK ‘N’ ROLL ROUTS RACKETEERS

Not willing to be intimidated or to give in to racketeers, Mike launched a dynamic, multi-faceted public relations campaign which he labeled “Rock ‘n’ Roll versus Racketeering.” As he puts it, “The chief executives of our biggest tube customers agreed to write letters on our behalf—Peavey and Fender here in the USA, Vox UK, Korg Japan. The letters were sent to important Russian officials including the Governor of Saratov, the Minister of Internal Affairs, the Chief Prosecutor and Putin’s appointee who was the head of the Volga region where our factory and RBE’s headquarters are located. The U.S. Embassy also worked closely with us and William Burns, U.S. Ambassador to Russia, sent letters to the Governor of Saratov and other high-level Russian government officials, voicing his concern and support for us.”

Mike appealed to Russia’s Anti-Monopoly Commission and Arbitration Court and won strong decisions from both, but RefEnergo shut off ExpoPul’s electric on March 29, 2006 boasting to Chinchikov that they’d succeed because they’d paid everyone off! On April 5, Saratov’s Governor Ipatov ordered ExpoPul and RBE to meet at government offices. The next day, as the Governor was getting electricity restored, the gas was shut off. Mike recalls, “Another appeal to the Governor got the gas turned back on, but Russian gangsters began loitering outside the factory while others used jackhammers to stir up dust and disrupt the tube making.”

On April 7, more than 800 ExpoPul workers wielding banners marched in front of the Saratov government complex to protest the attempted takeover. Interviews and articles in the Moscow Times, New York Times, MSNBC and many dozens of music and mainstream media brought additional focus on the struggle. Mike’s voice—and the voices of the ExpoPul workers—were being heard.

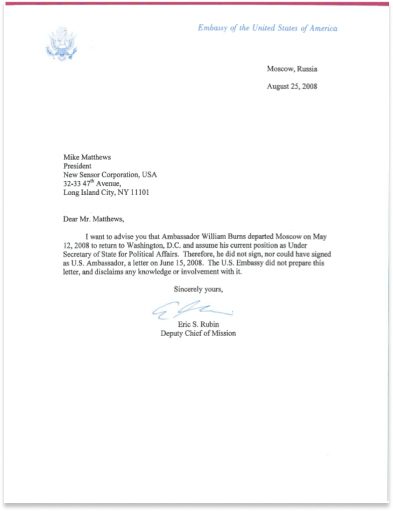

Nevertheless, the struggle did not end there. RBE sold their Reflektor holdings, including RefEnergo, to another nefarious organization, SDM, Samara Business World. SDM also engaged in cutting off the factory’s energy resources and sued ExpoPul for “stealing” hydrogen. In their attempts to create a maelstrom of negative public opinion, and trying ultimately to force Mike to sell, they created stories about an American spy network in Saratov and how the region had been influenced by American interests. They went so far as to publish a forged letter from the U.S. Ambassador to Russia, William Burns. The State Department confirmed it was a forgery and described how Ambassador Burns had actually left his post in Russia before the date the letter was allegedly written and signed! Ambassador William Burns was confirmed as Director of the Central Intelligence Agency on March 18, 2021.

Ultimately, right would prevail and the theme would shift to Rock ‘n’ Roll Routes Racketeers… but only after a tough fight. Sadly, Saratov’s Chief Prosecutor who supported the workers at ExpoPul was assassinated and paid for the victory with his life. It brought a somber new meaning to the phrase “hostile takeover attempt.”

Read more…

2006

THE ROAD TO STALINGRAD

I wanted to honor the surviving

veterans of the Stalingrad battle and celebrate our own victory.

2006

THE ROAD TO STALINGRAD

Mike’s a student of history and well-versed on World War II, including battles fought by the Russians and Nazis. He’s also an avowed admirer of General Georgy Zhukov, the preeminent Russian military leader who oversaw many of the Red Army’s most decisive victories including those at Stalingrad and Kursk.

After ExpoPul thwarted the racketeer’s illicit takeover attempts, Mike sponsored two celebratory trips by Saratov older teenagers, the children of ExpoPul workers, to visit historical cities in the Soviet Union. For the first, a busload traveled from Saratov to Stalingrad, the location of one of the longest and bloodiest engagements in modern warfare. As Mike explains, “About two million people were killed or injured, but the Battle of Stalingrad (August 23, 1942 – February 2, 1943) ultimately turned the tide of World War II {referred to by the Russians as The Great Patriotic War} in favor of the Allies. I wanted to honor the surviving veterans of the Stalingrad battle and celebrate our own victory. The teens wore tee shirts emblazoned with the inscription, ‘Rock & Roll Routs Racketeers.’” They toured historic sites, visited the Veterans’ Hospital and gave presents to all the surviving veterans of the Battle of Stalingrad. Old and young met and mingled as the different generations had a chance to connect.”

The Battle of Kursk took place during the summer of 1943, after the Battle of Stalingrad. As Mike explains, “It was the largest mechanized battle in history. Some 6,000 tanks, thousands of cannons and rocket launchers, 4,000 aircraft and 2,000,000 troops were involved. The Russians, relying on important intelligence information, were well prepared and their victory marked the decisive end of the German offensive capability on the Eastern Front. It was Hitler’s last gasp and the Nazis never recovered.”

Two busloads of students from ExpoPul, plus a Saratov rock & roll band, made the ten-plus hour trip from Saratov where they were hosted by the University of Kursk. The occasion was Victory Day, the Russian holiday commemorating victory over the Nazis. With a rock band from Kursk joining the festivities, students from Saratov and Kursk partied together in the university’s arena as they celebrated Victory Day and ExpoPul’s victory in Rock & Roll Routs Racketeers.

The next day, they toured the city, visited the local Veterans’ Hospital and brought presents to the surviving soldiers. Mike explains, “As with our visit to Stalingrad, I wanted to honor the survivors of the historic battle that took place in Kursk and also celebrate our factory’s fight to prevail, and provide ongoing employment to its 800 plus workers.”

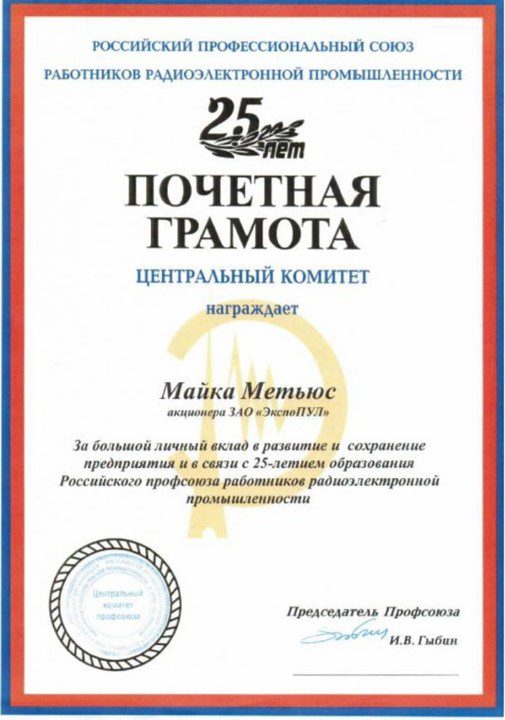

Awarded to Mike Matthews on November 20th, 2016

EHX &

MIKE TODAY

Mike Matthews,

getting down on the Overlord

MIKE’S ROAD TO SUCCESS

My favorite pedals are the hottest sellers!

MIKE’S ROAD TO SUCCESS

As described earlier, Mike Matthews first entered the effects pedal business in 1967 with the Foxey Lady fuzz he built for Guild. A year later Mike quit his job at IBM and launched Electro-Harmonix and the iconic LPB-1 Linear Power Booster. In the following half-century plus, the company’s product range has grown beyond what anyone might have imagined. There were only a few different types of effects available in the late 1960s and even fewer competitors with a handful of pedal makers vying in the marketplace. Now, as of this writing (2021), the company offers over 150 active Electro-Harmonix products including pedals, amps, strings, etc. and over 360 vacuum tubes! It’s a remarkable accomplishment when one considers Mike’s and EHX’s humble beginnings.

When asked to name his favorite pedals, Mike invariably answers, “My favorites are the ones that are selling!” With that in mind, here are some of the biggest hits the company has enjoyed over the years.

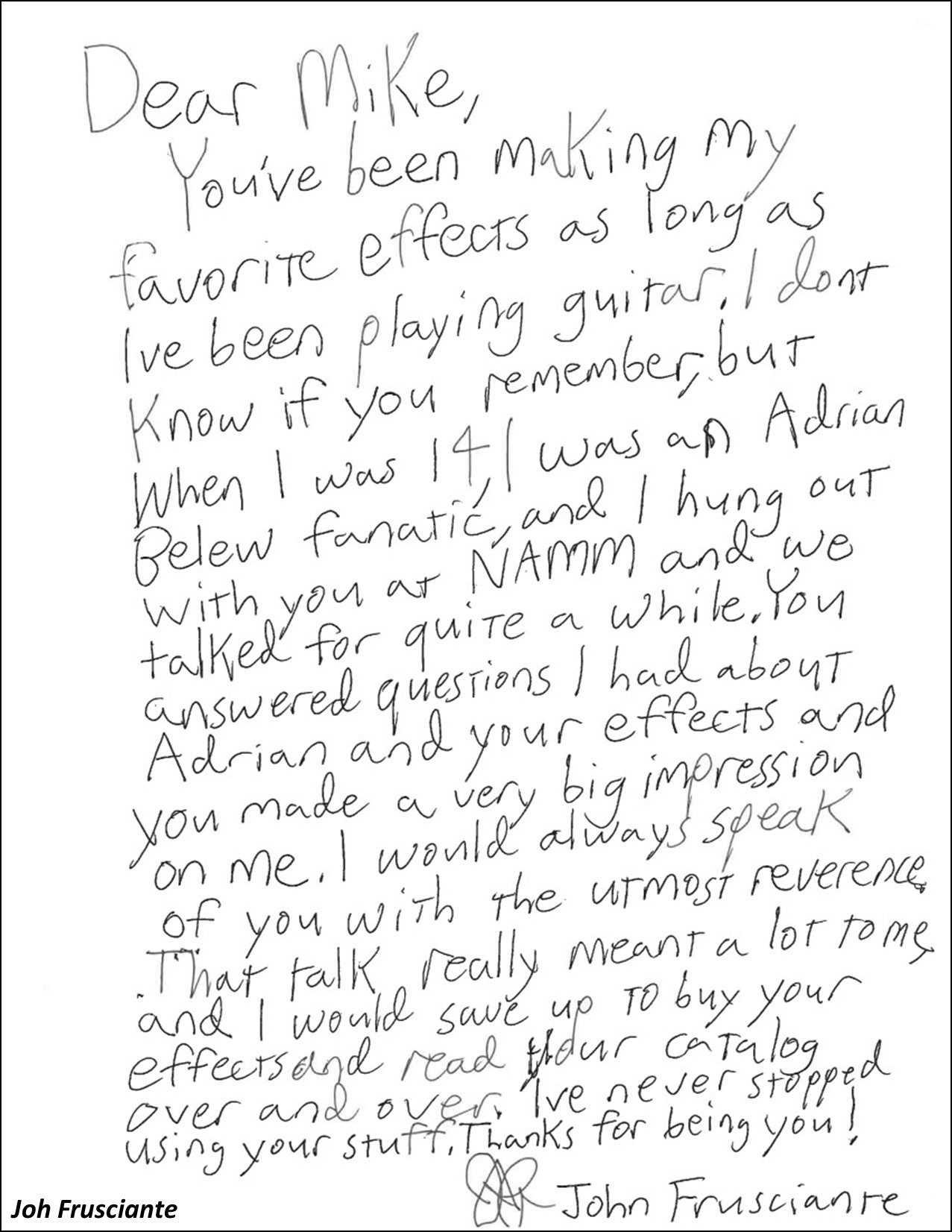

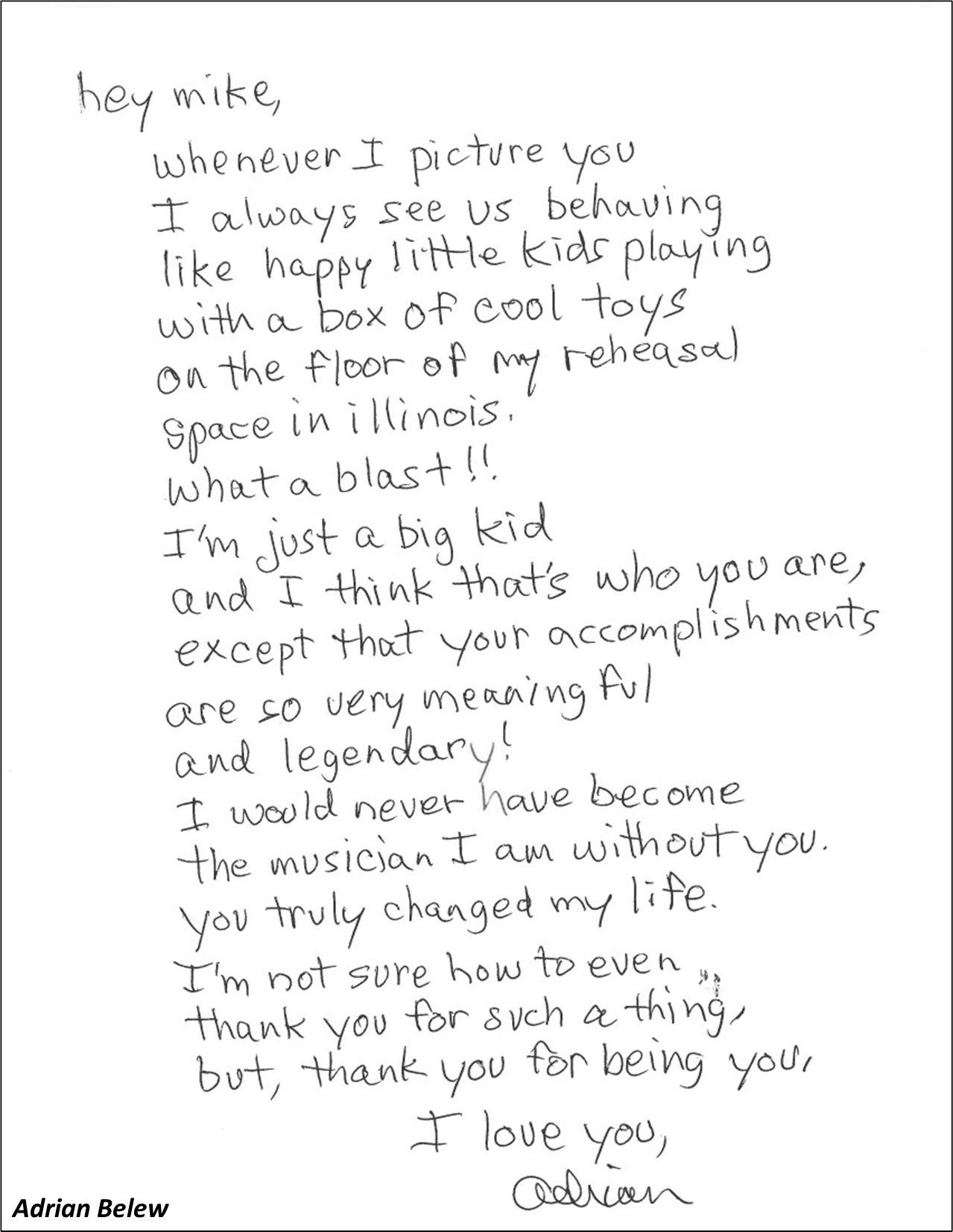

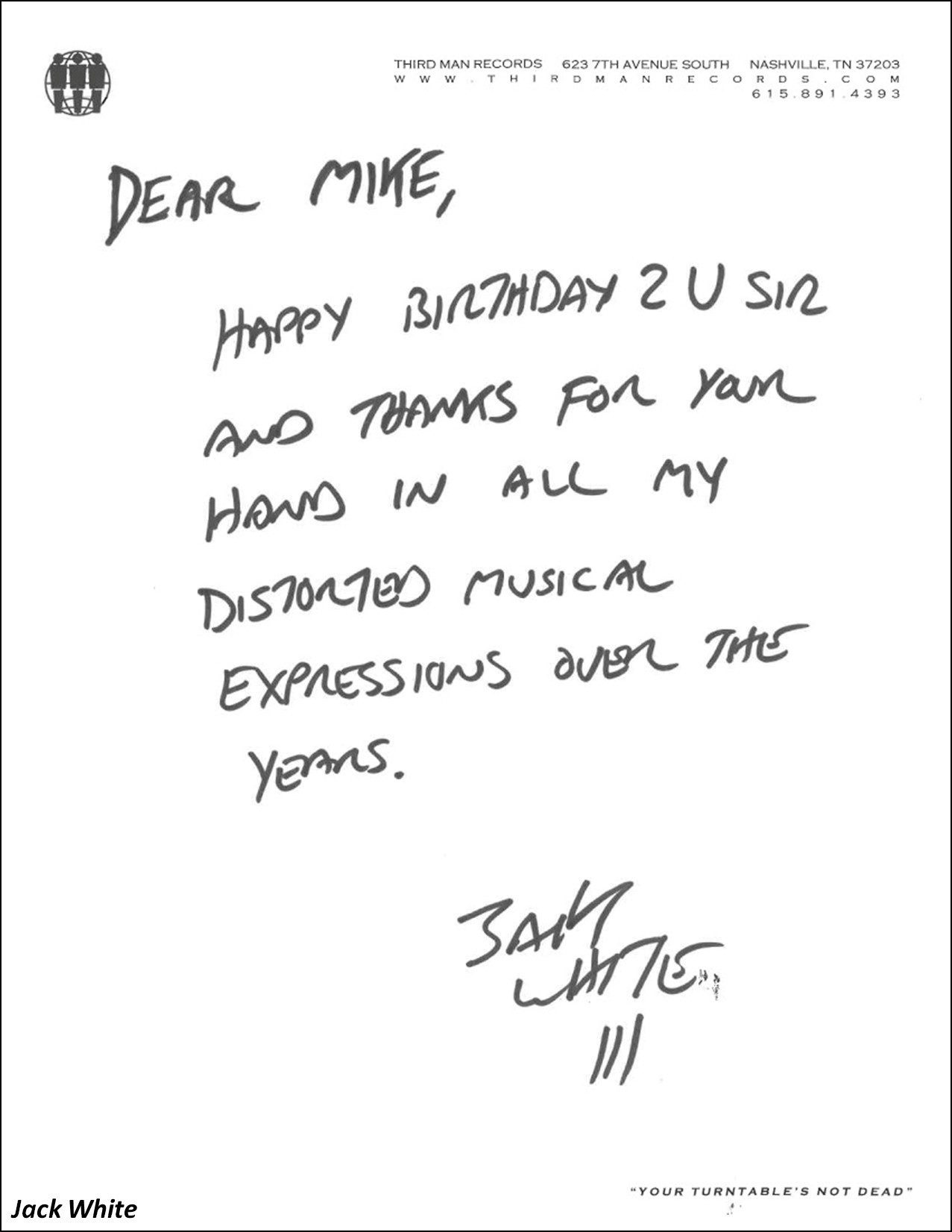

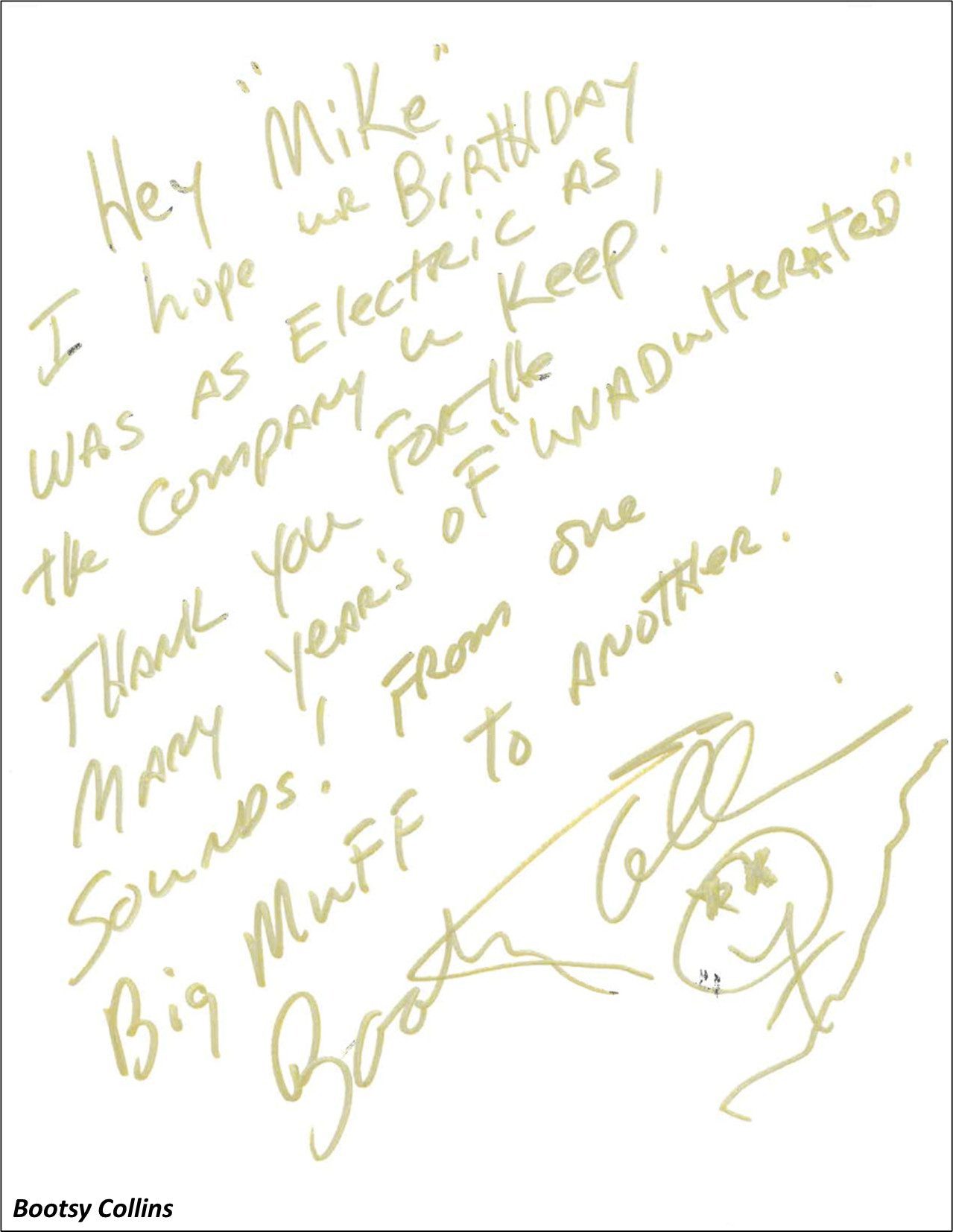

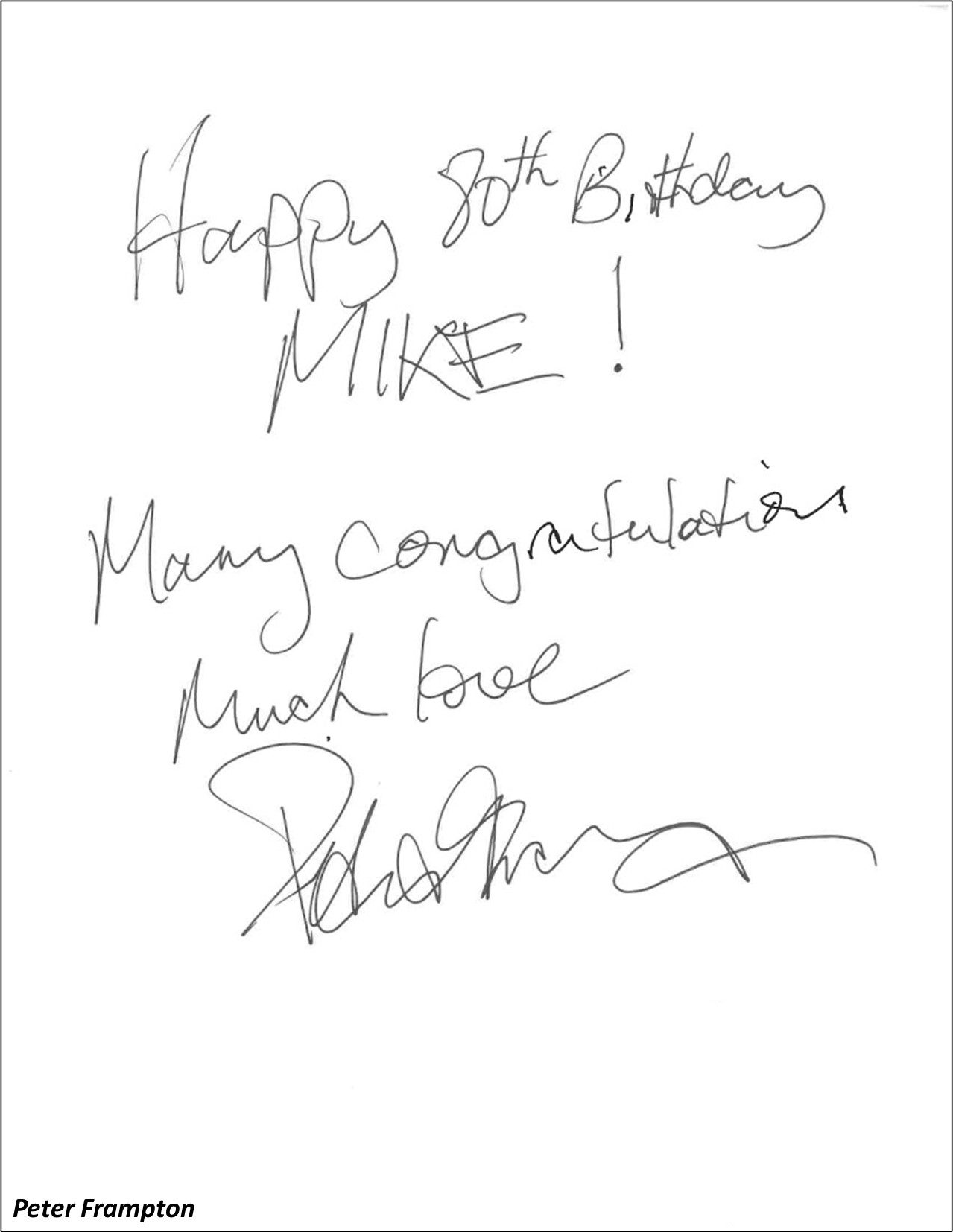

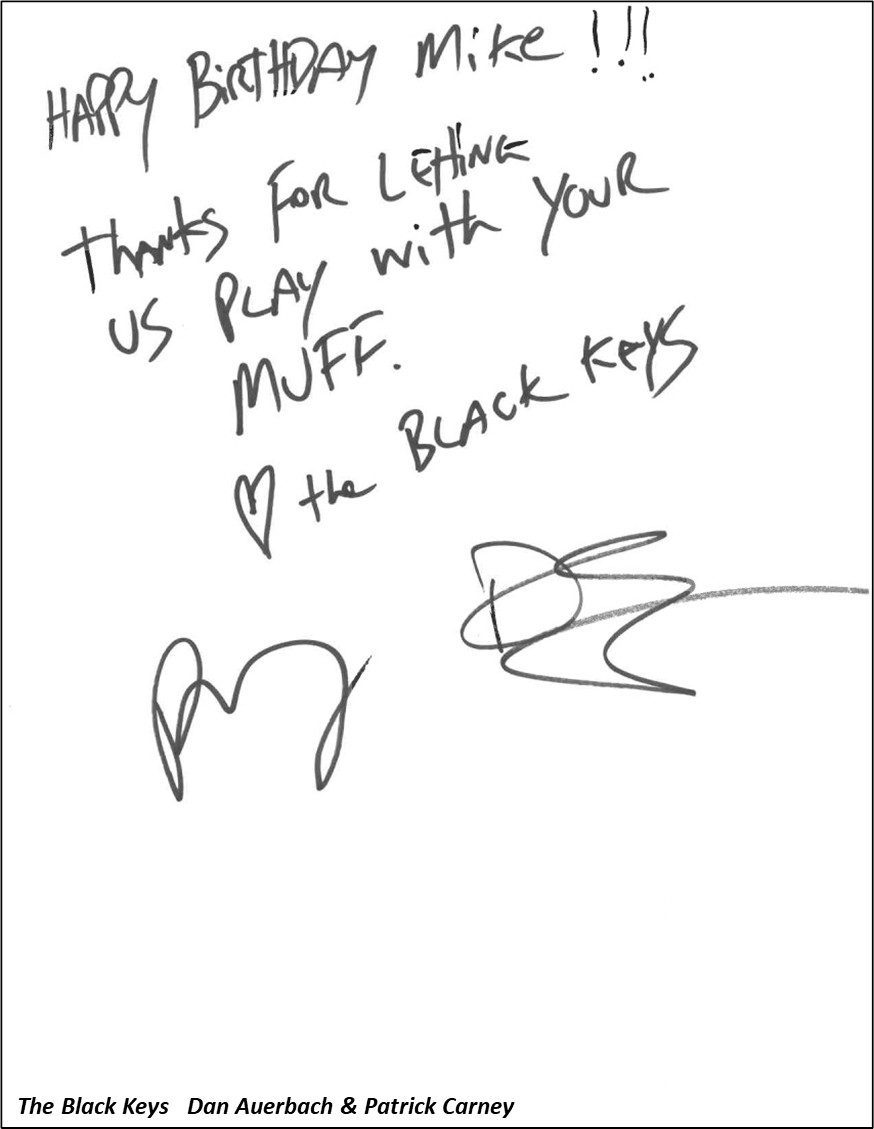

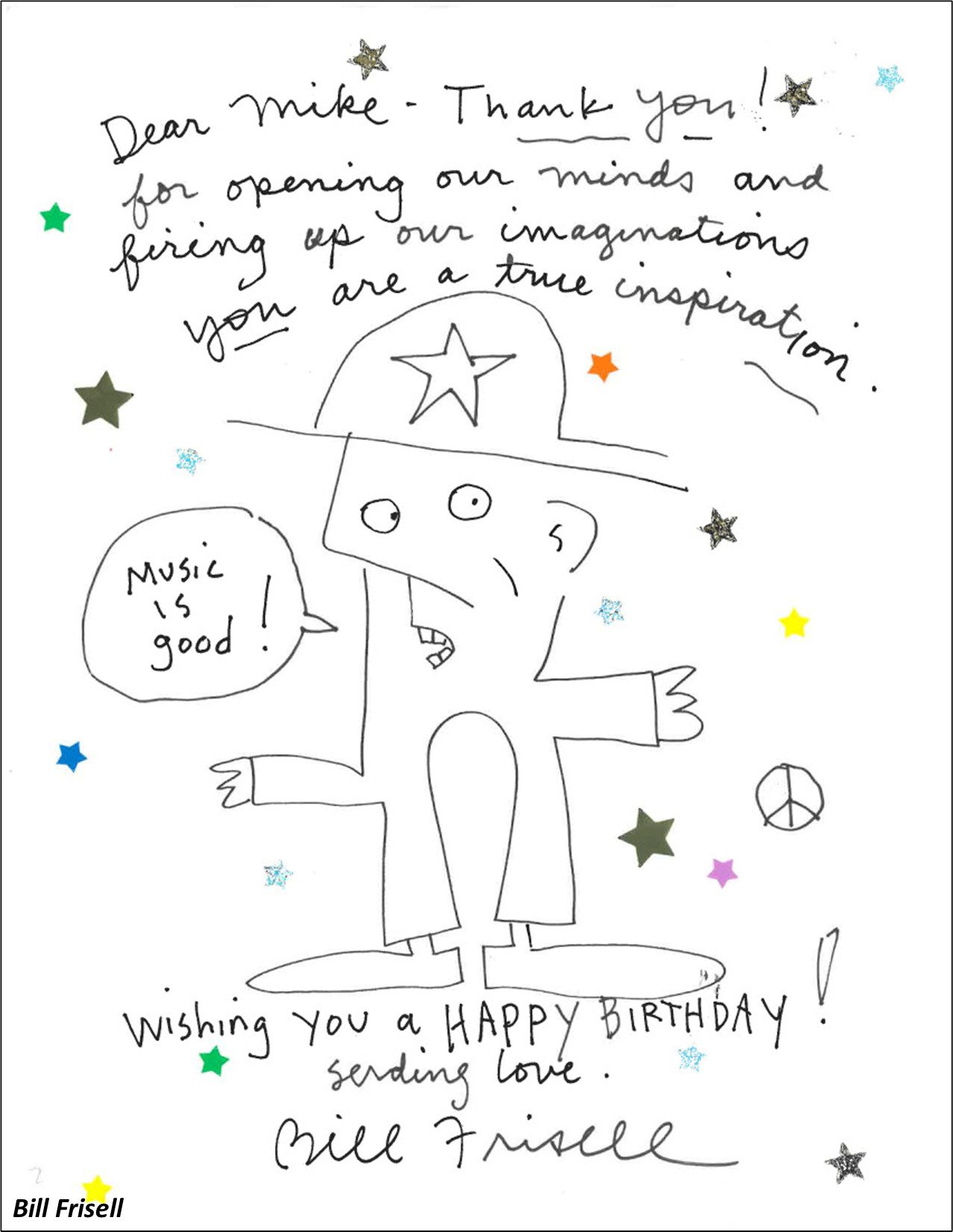

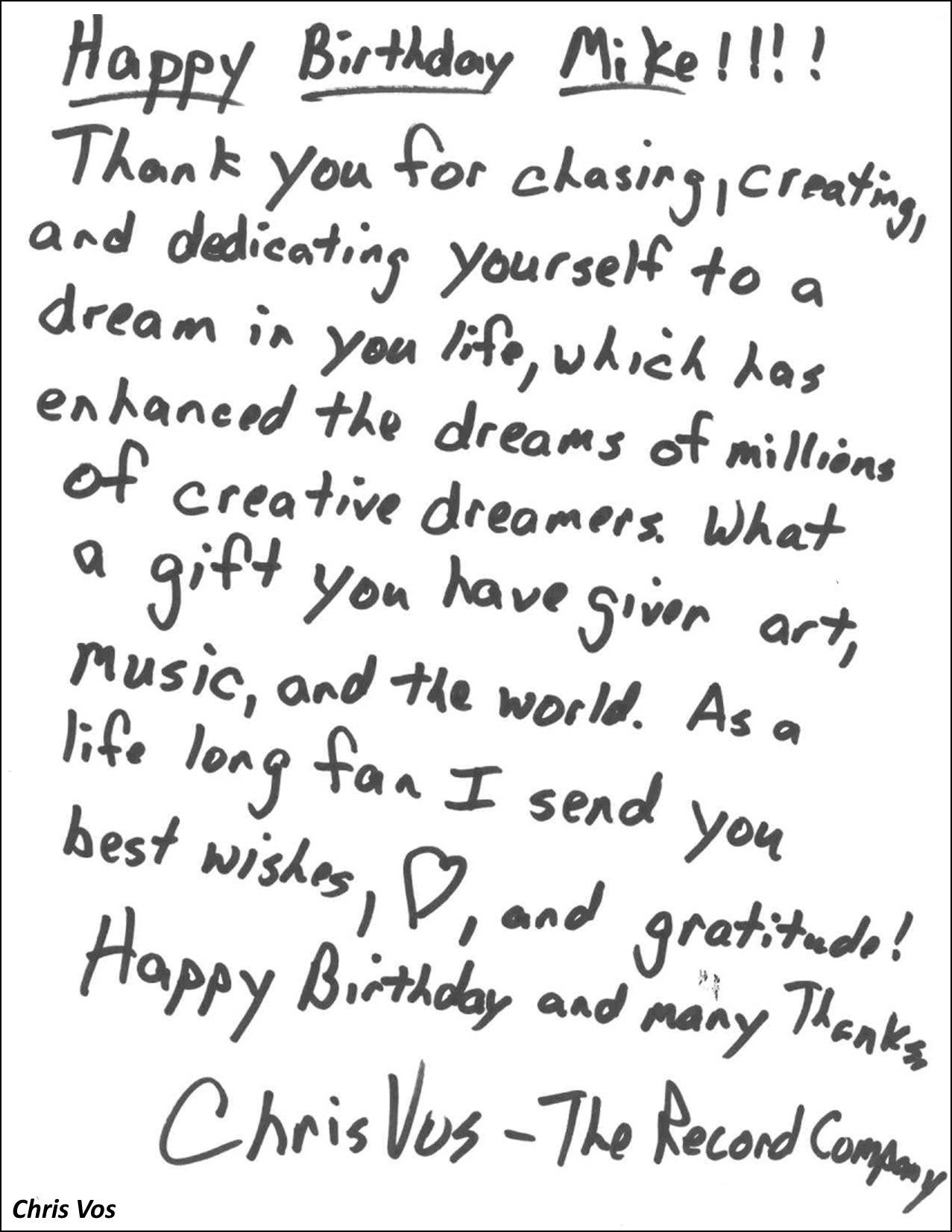

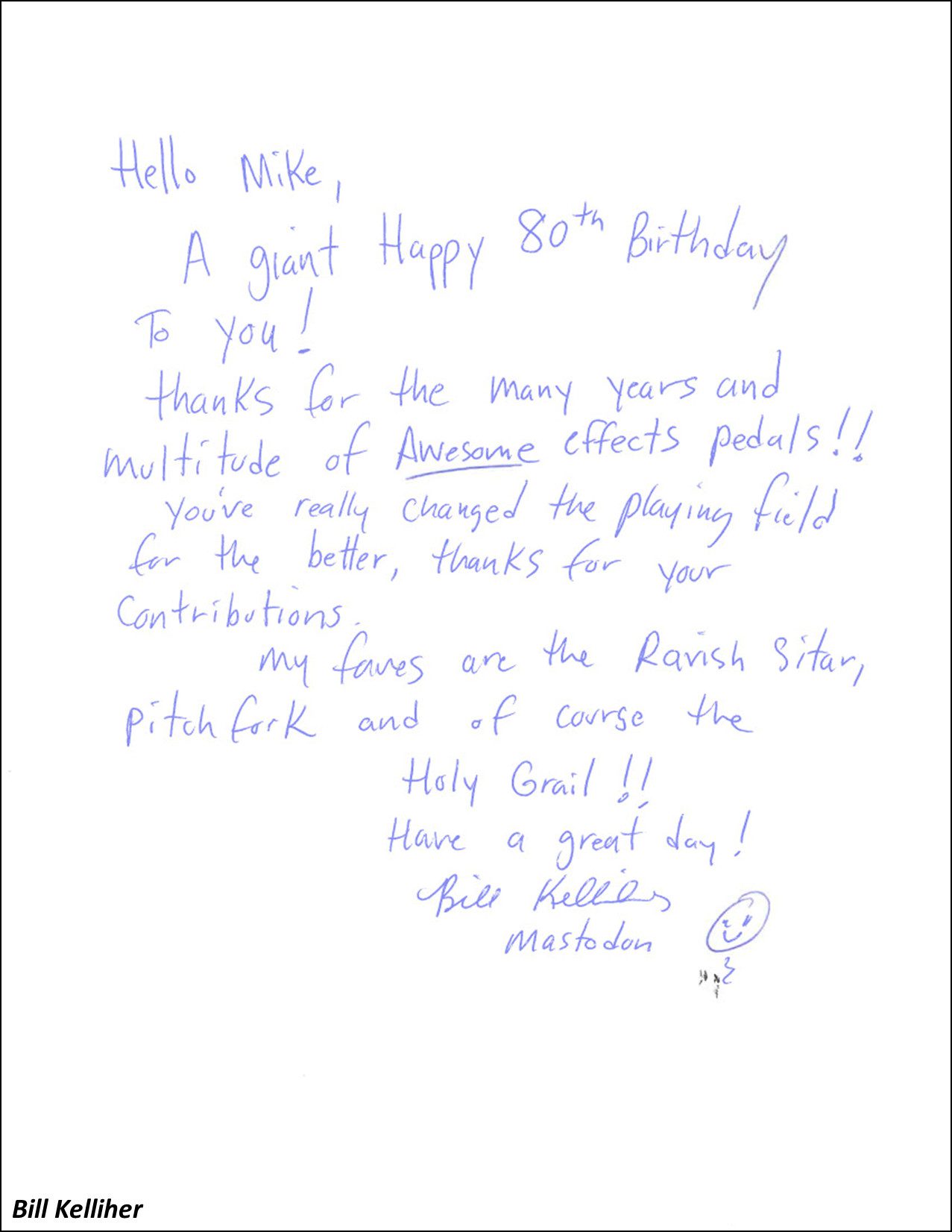

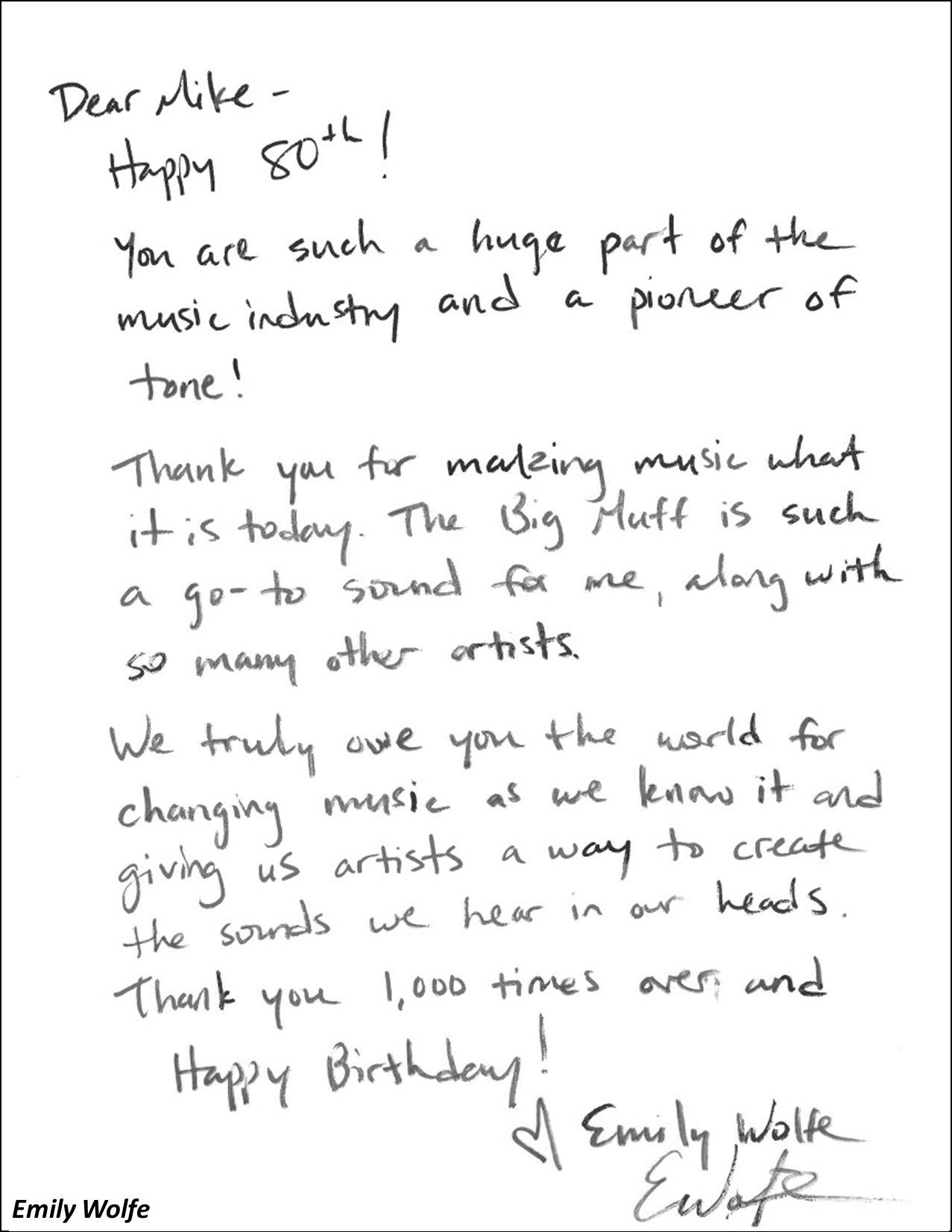

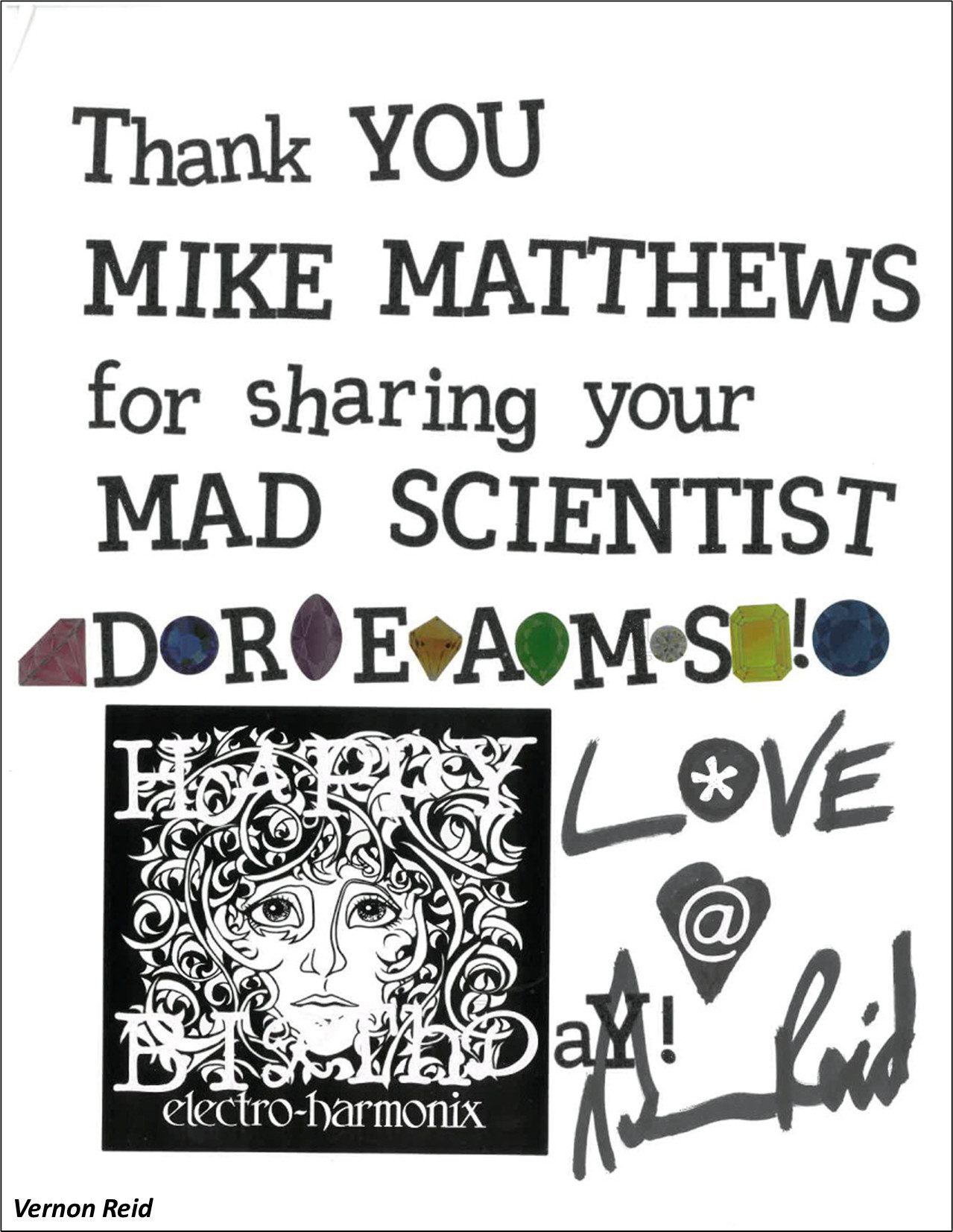

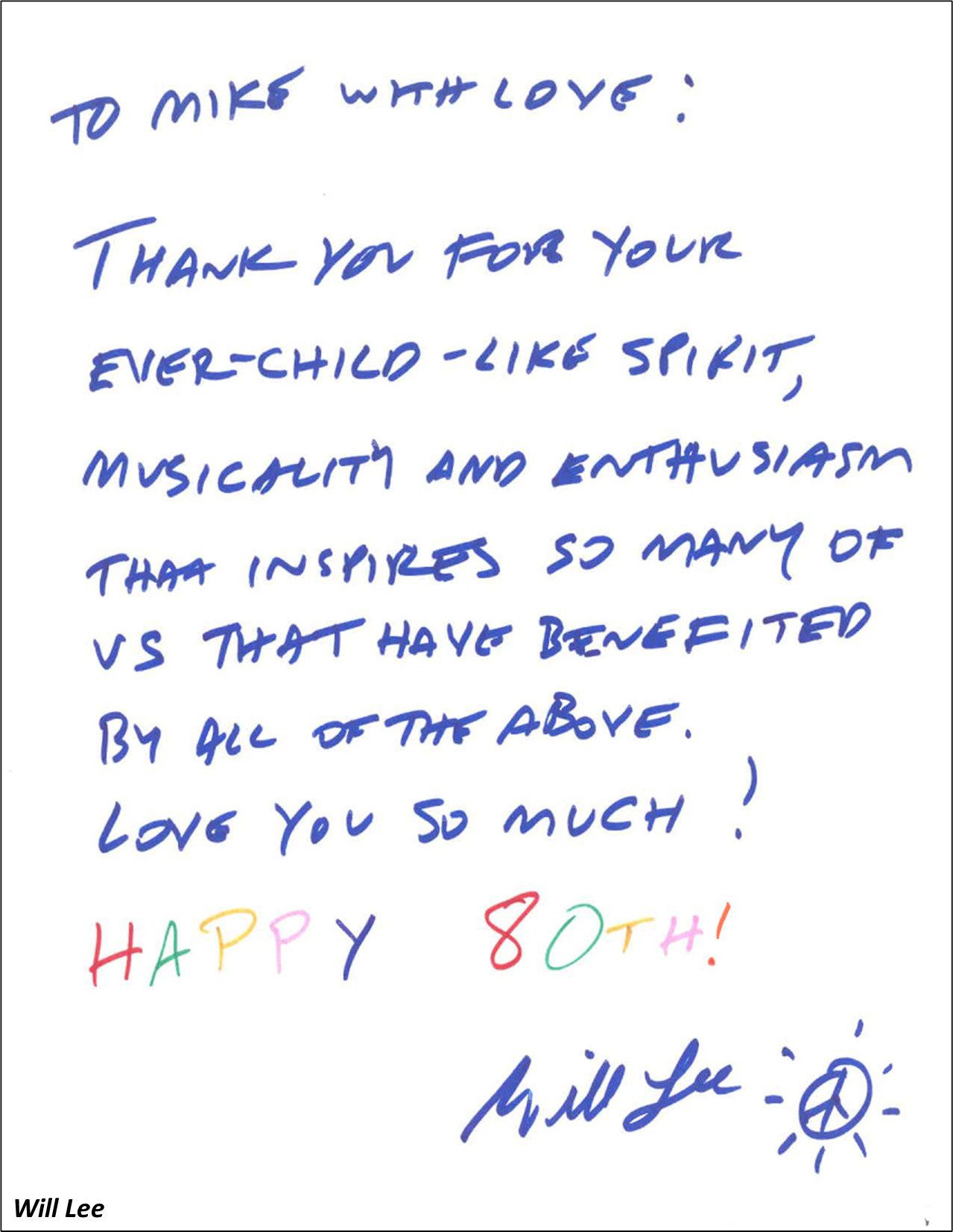

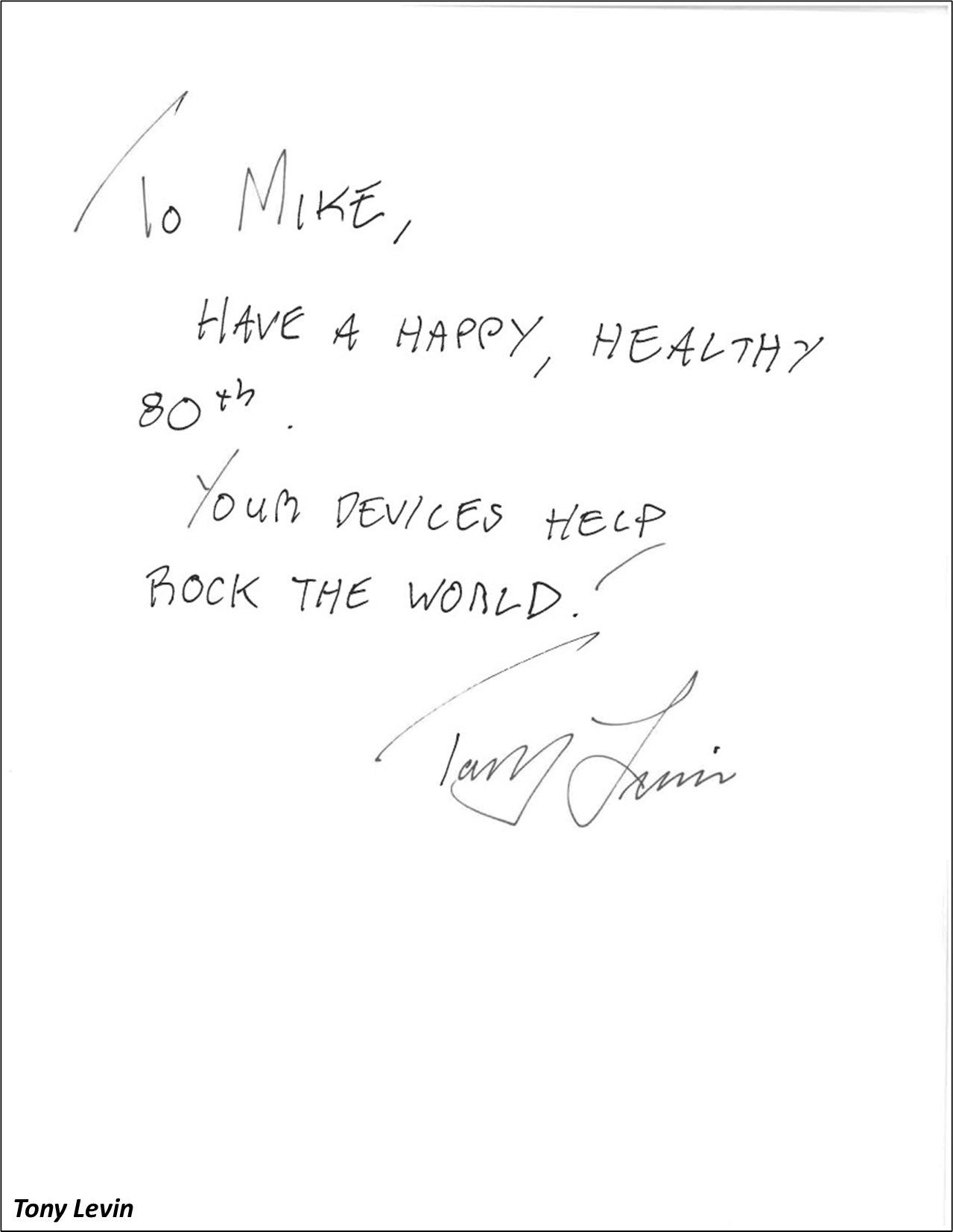

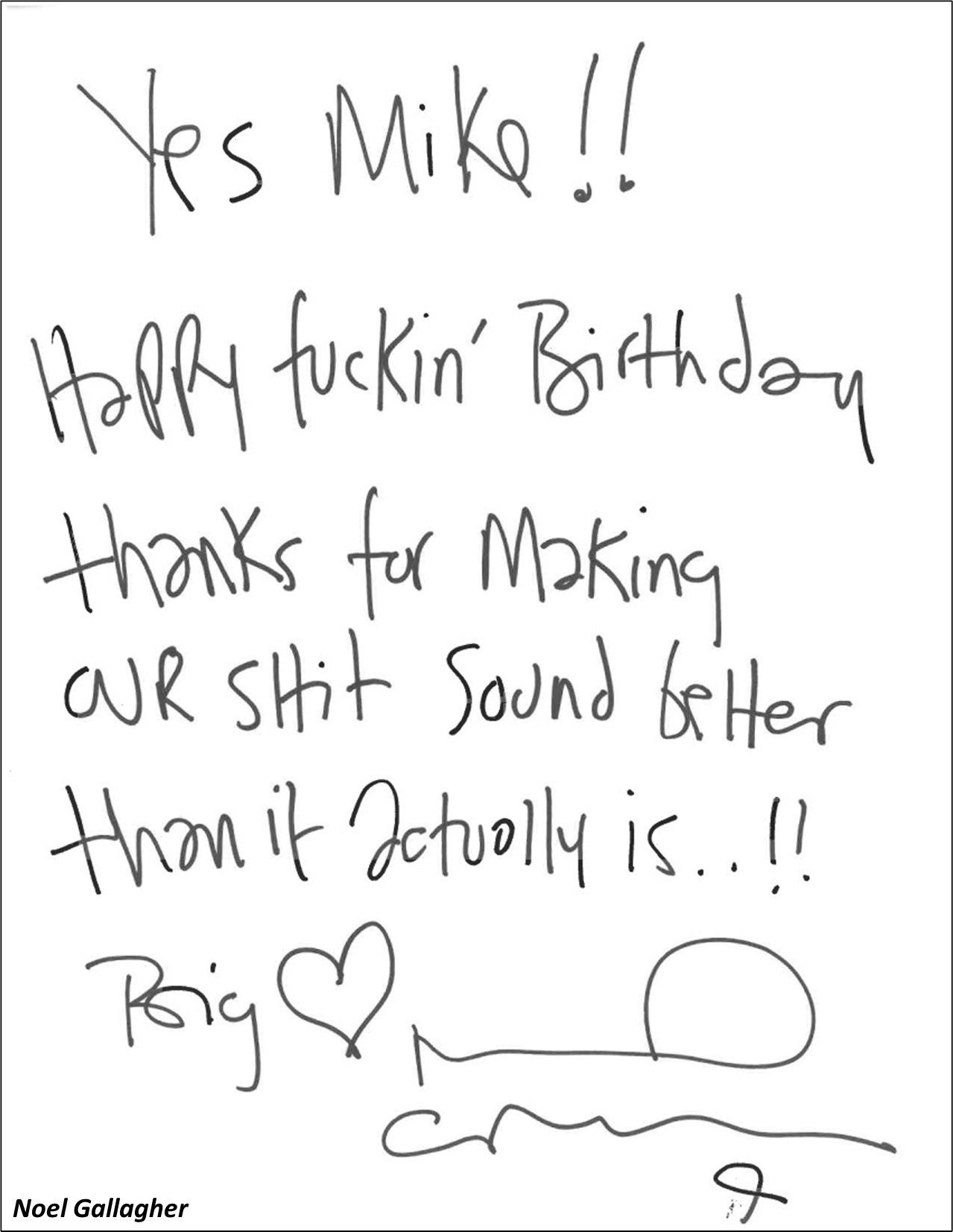

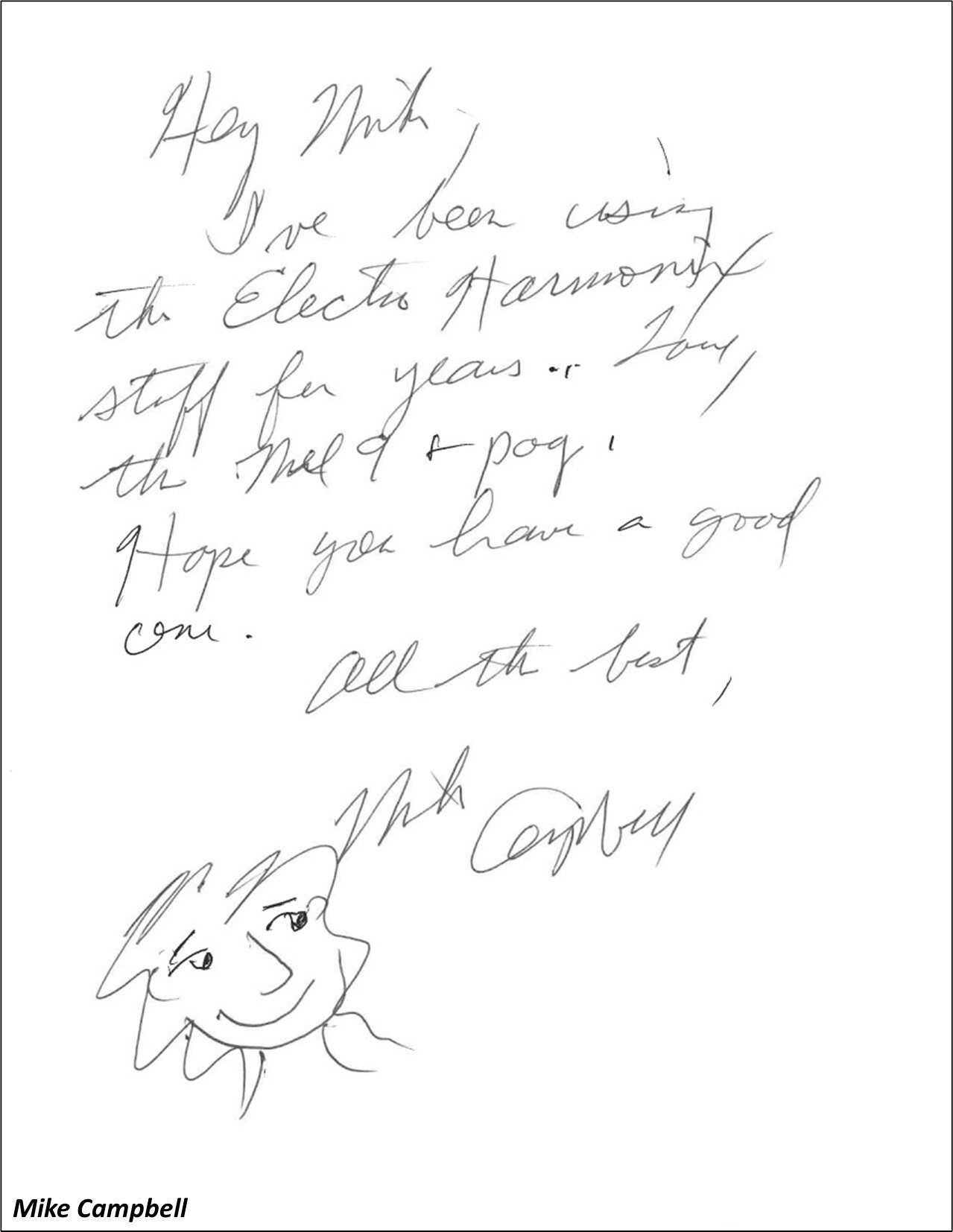

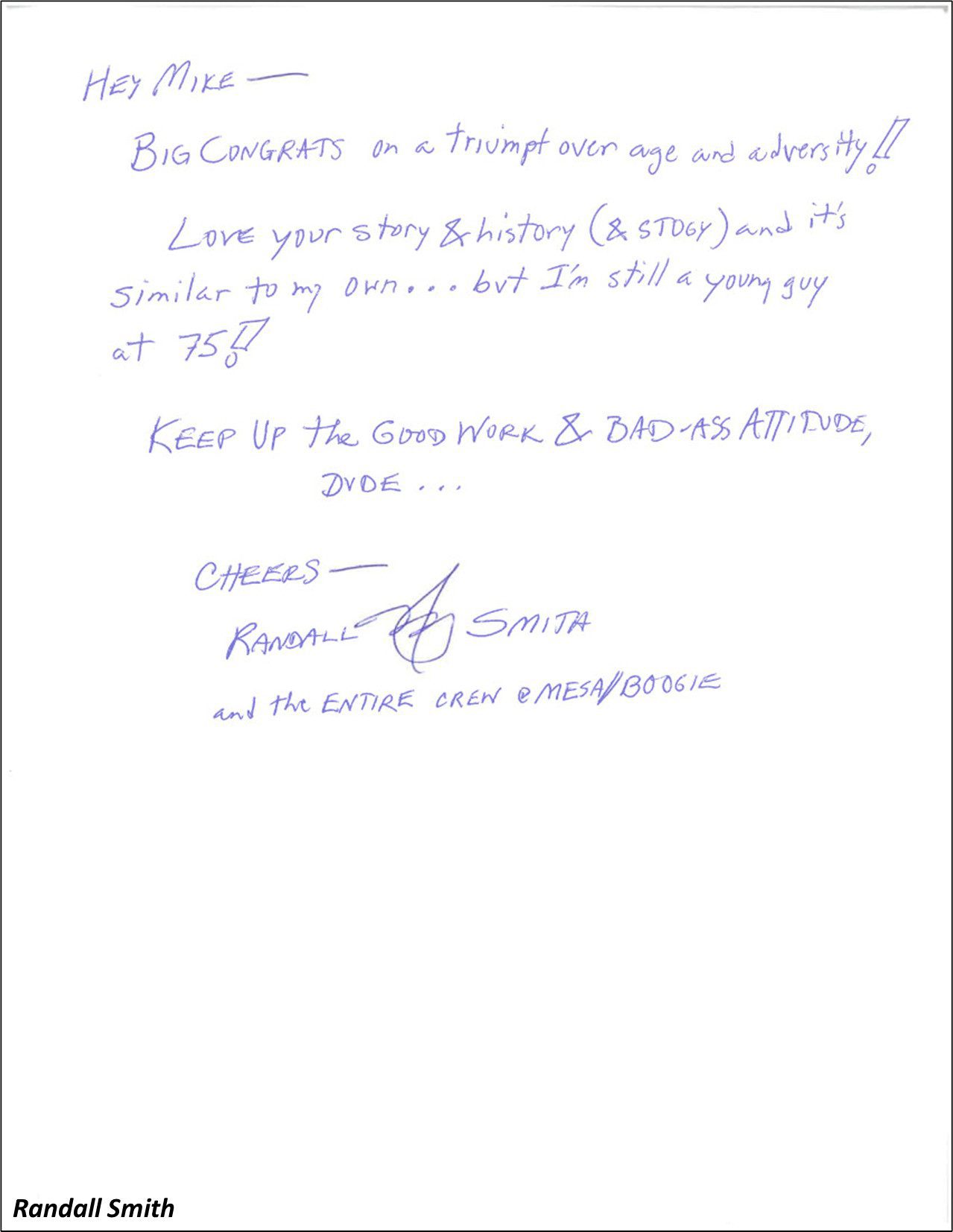

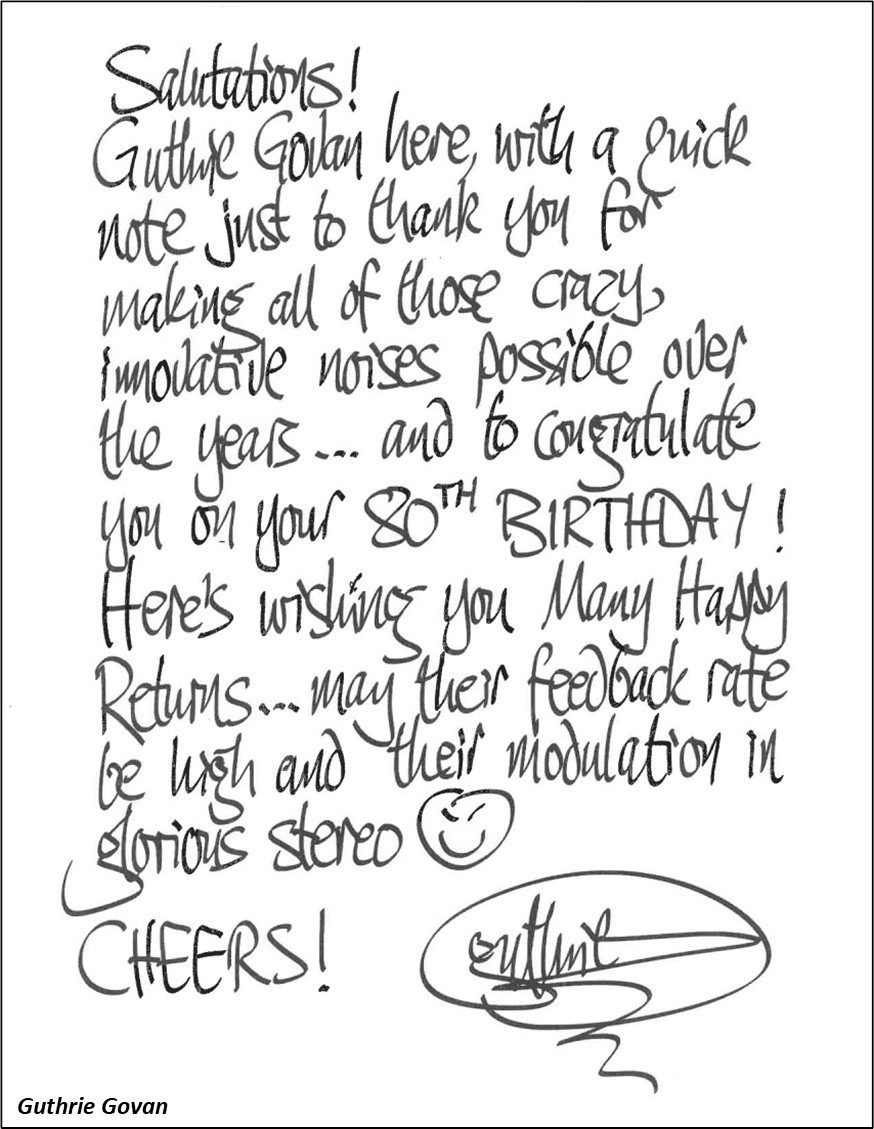

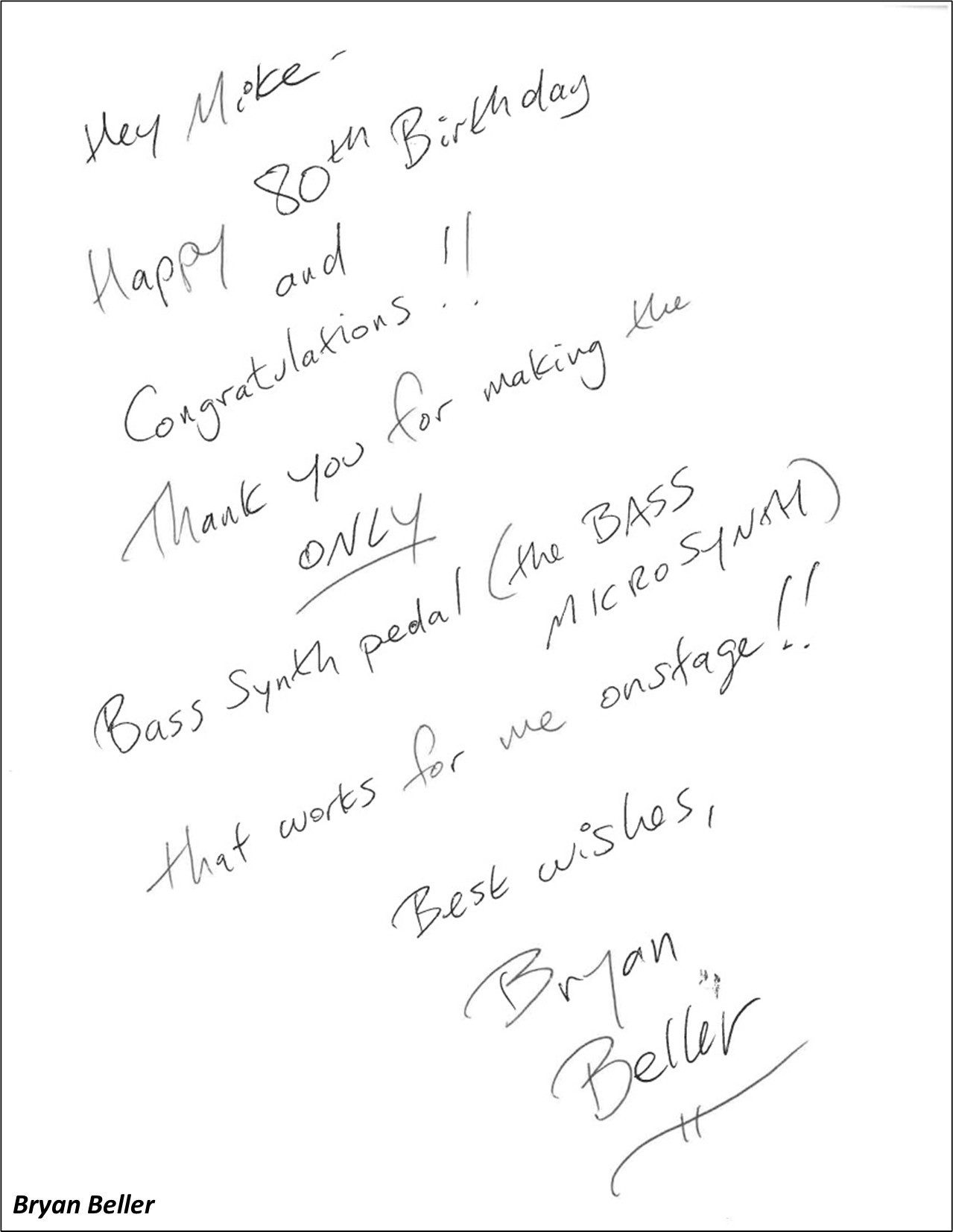

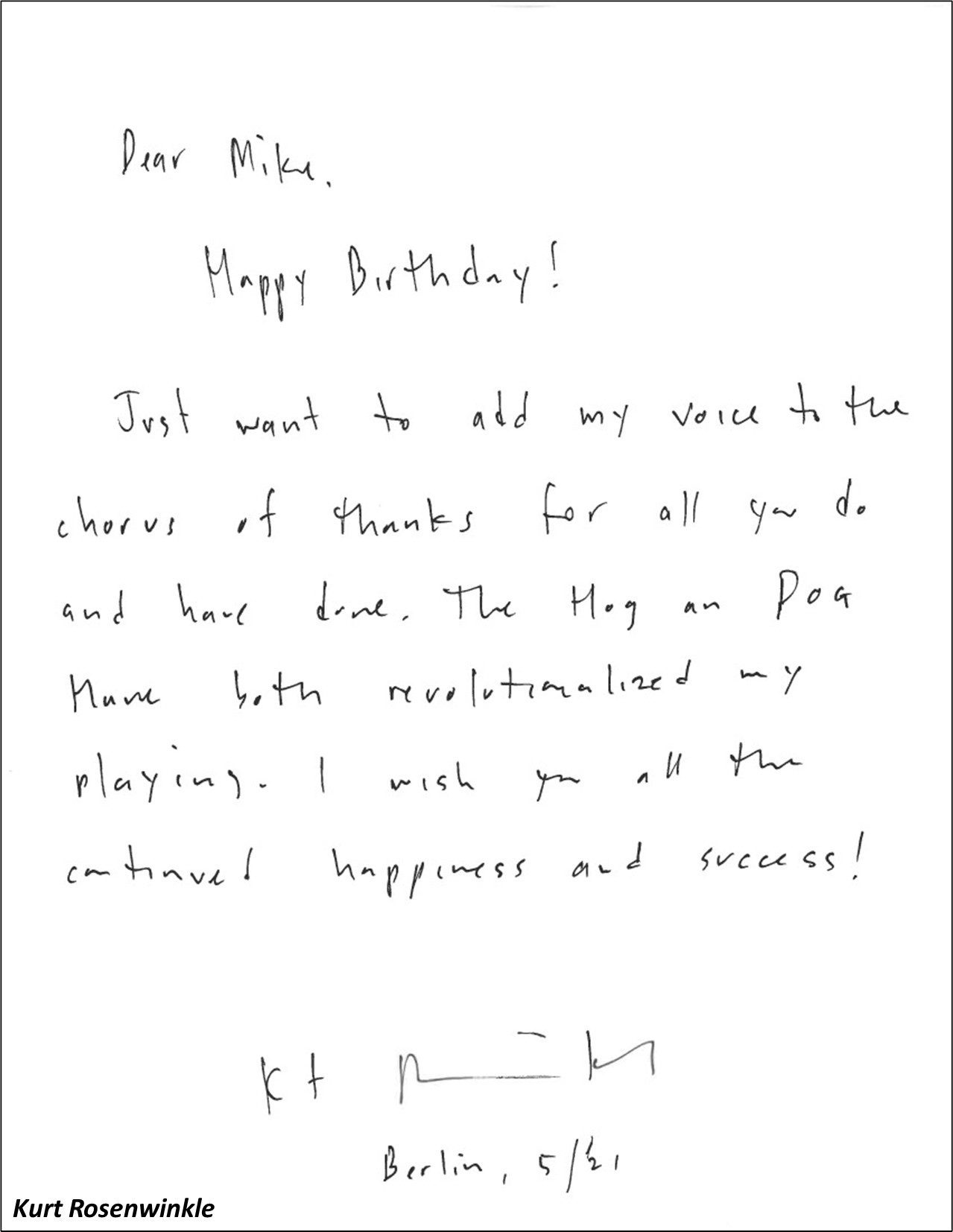

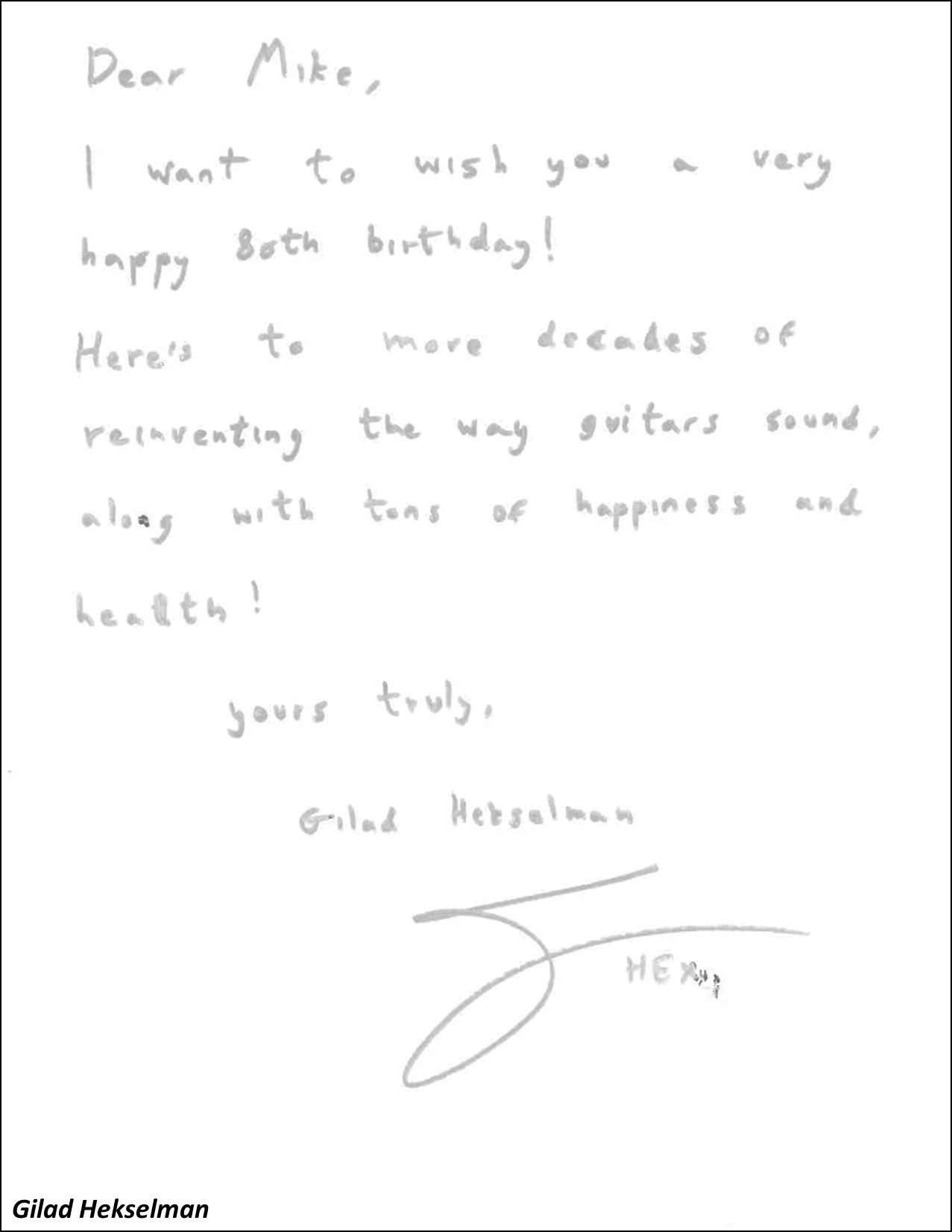

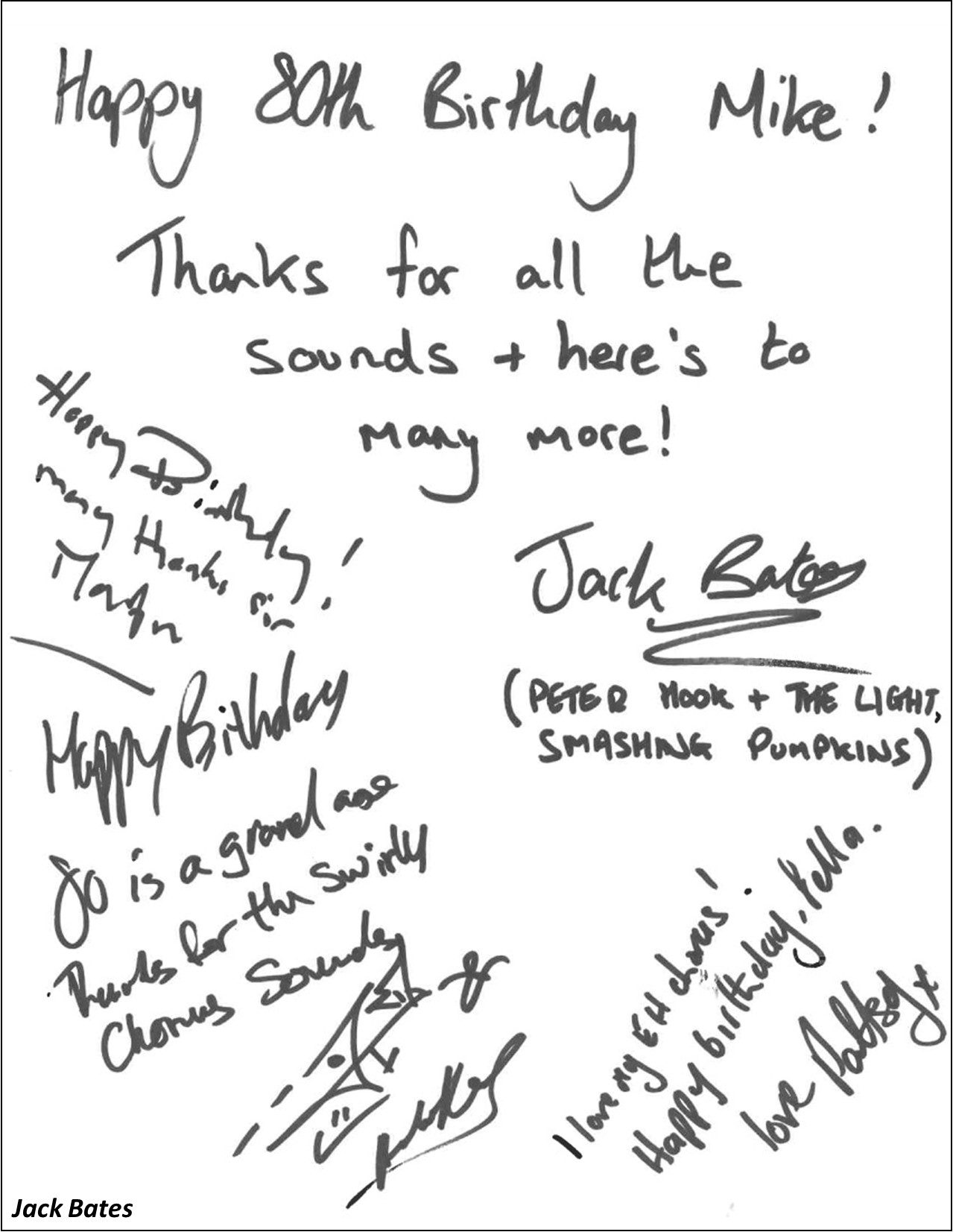

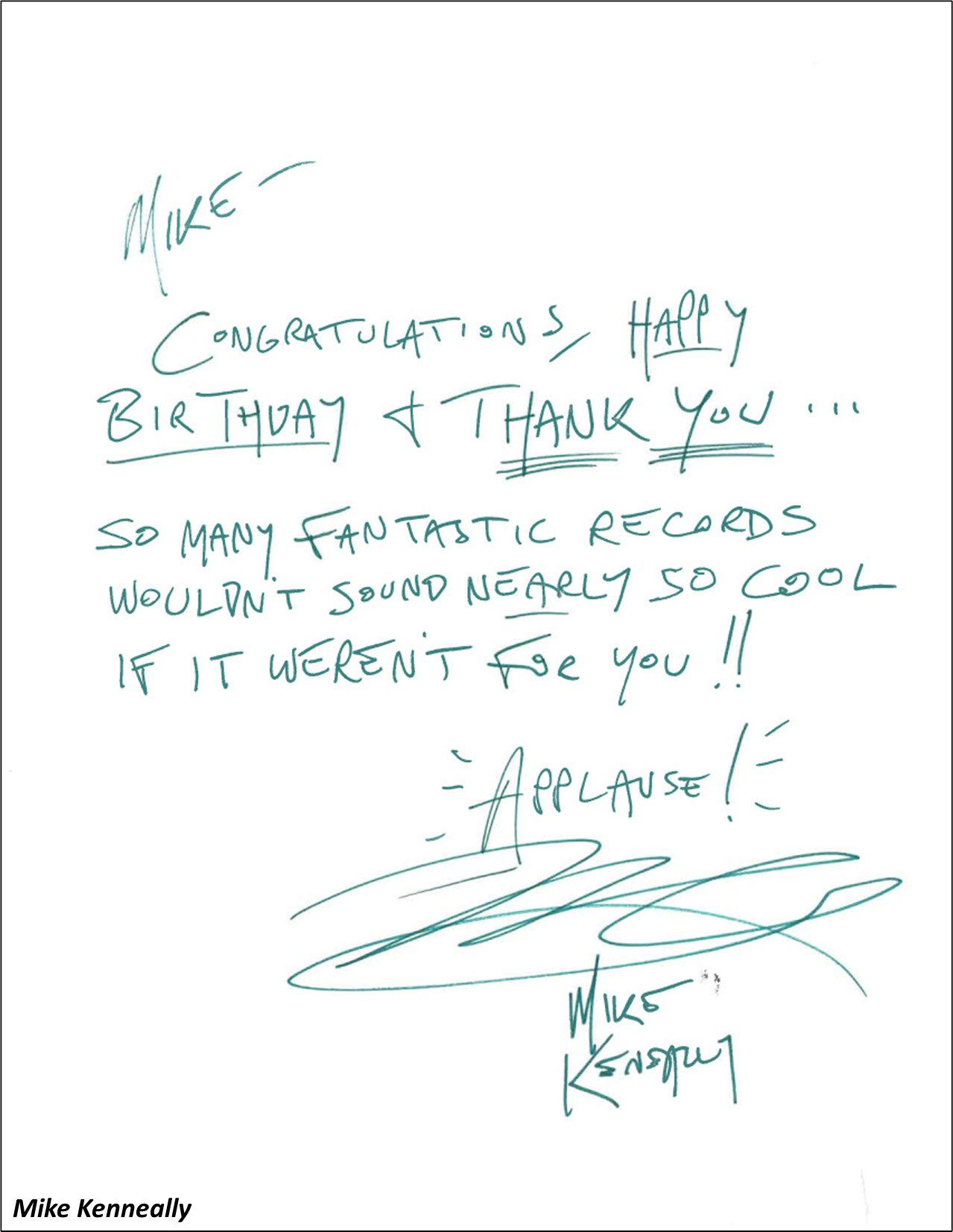

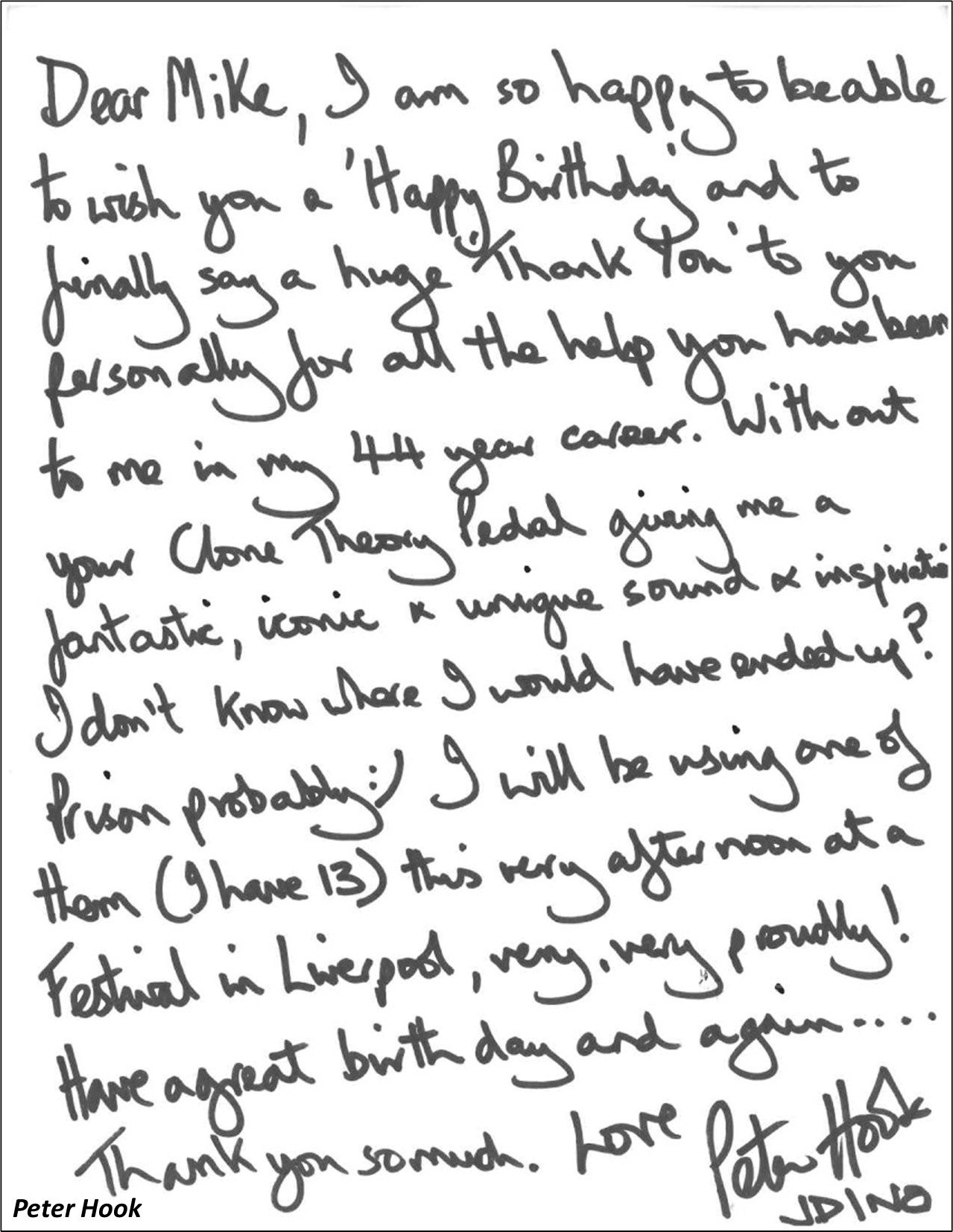

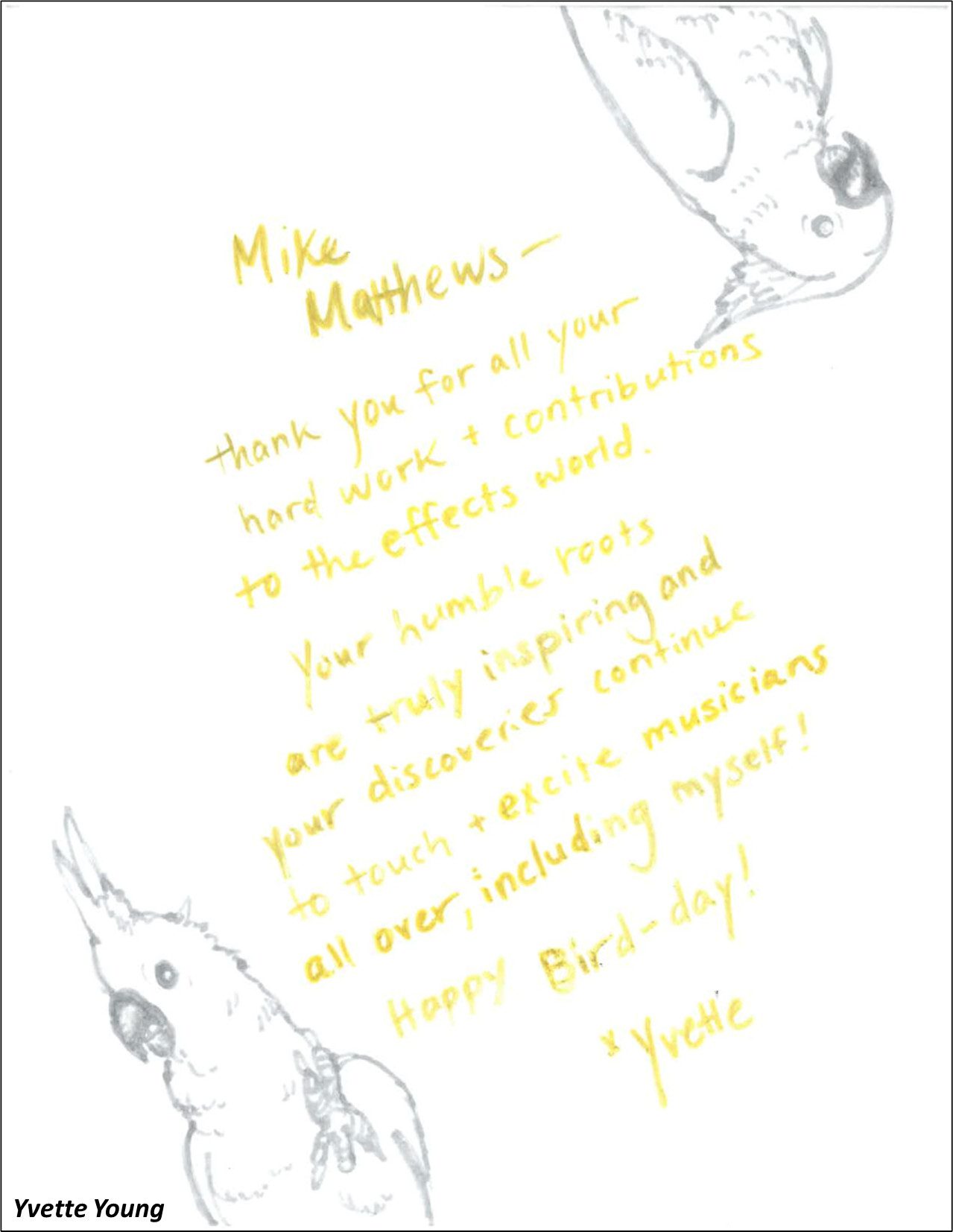

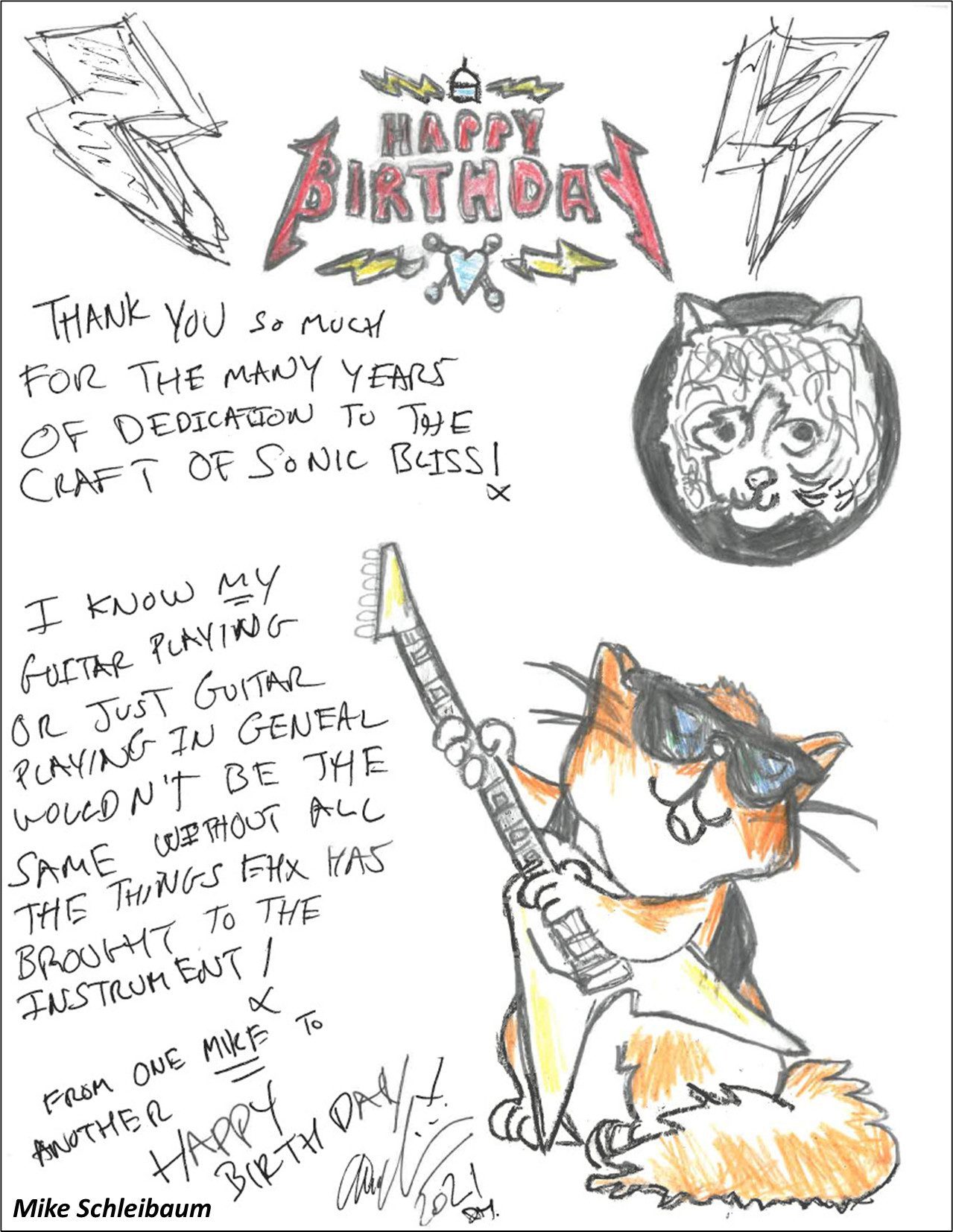

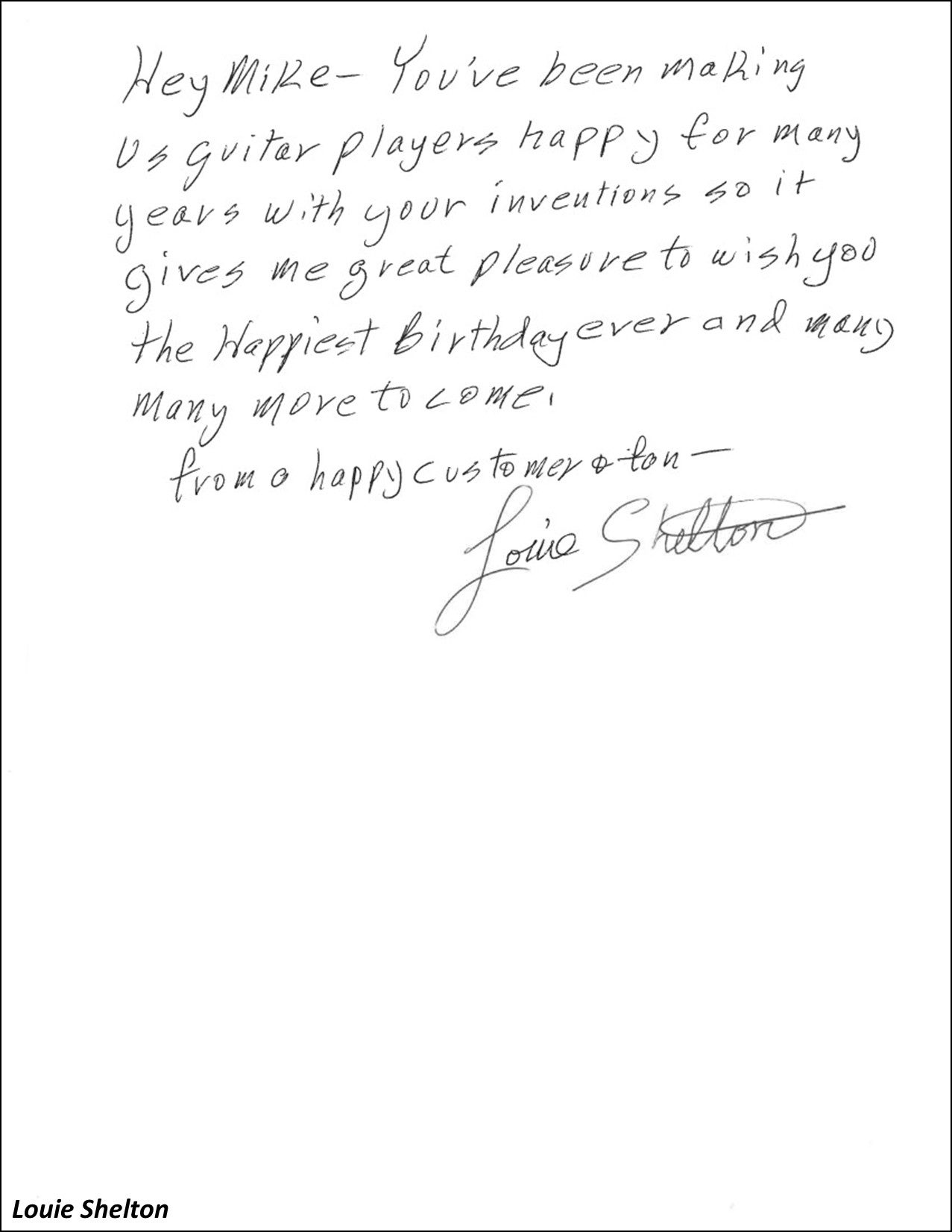

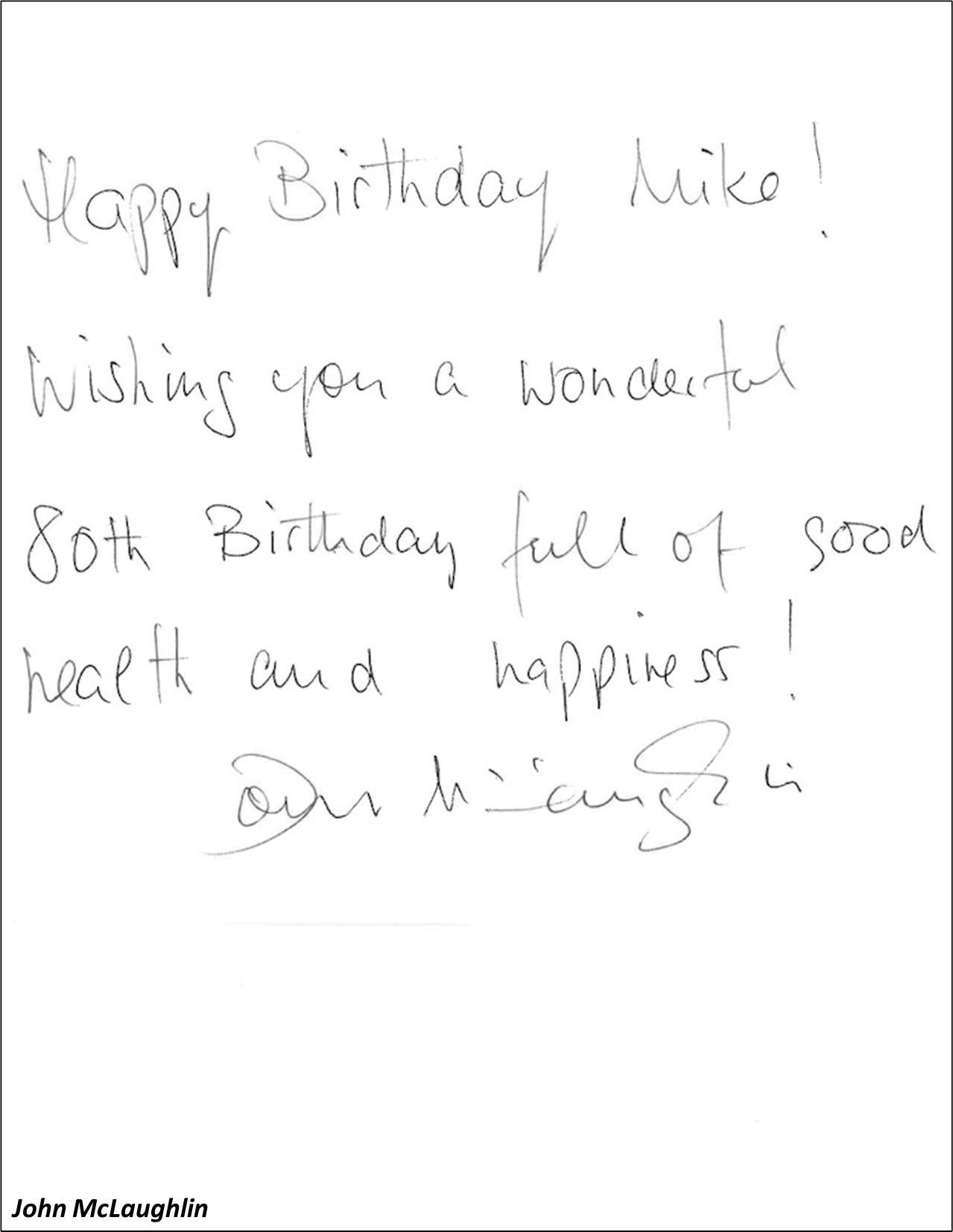

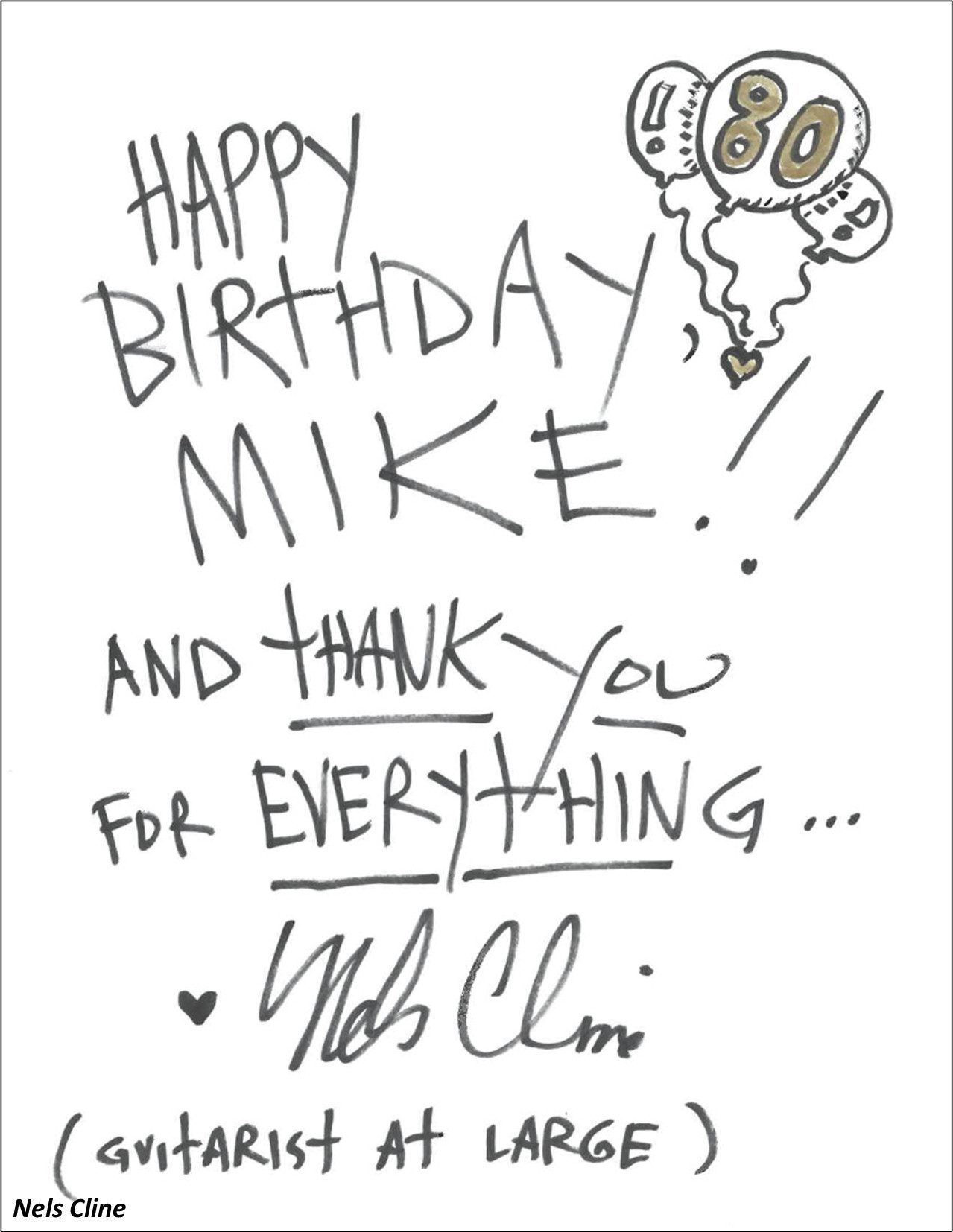

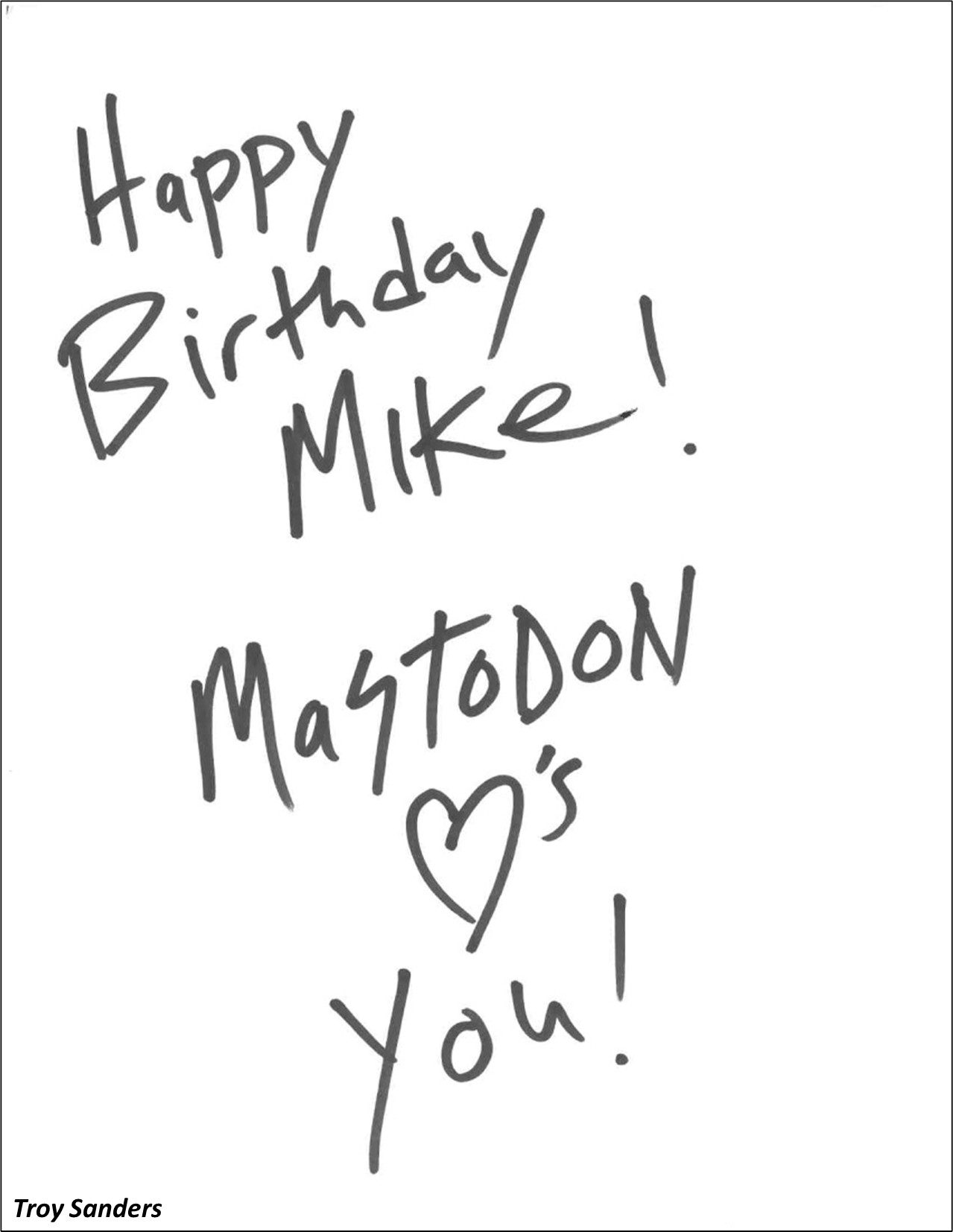

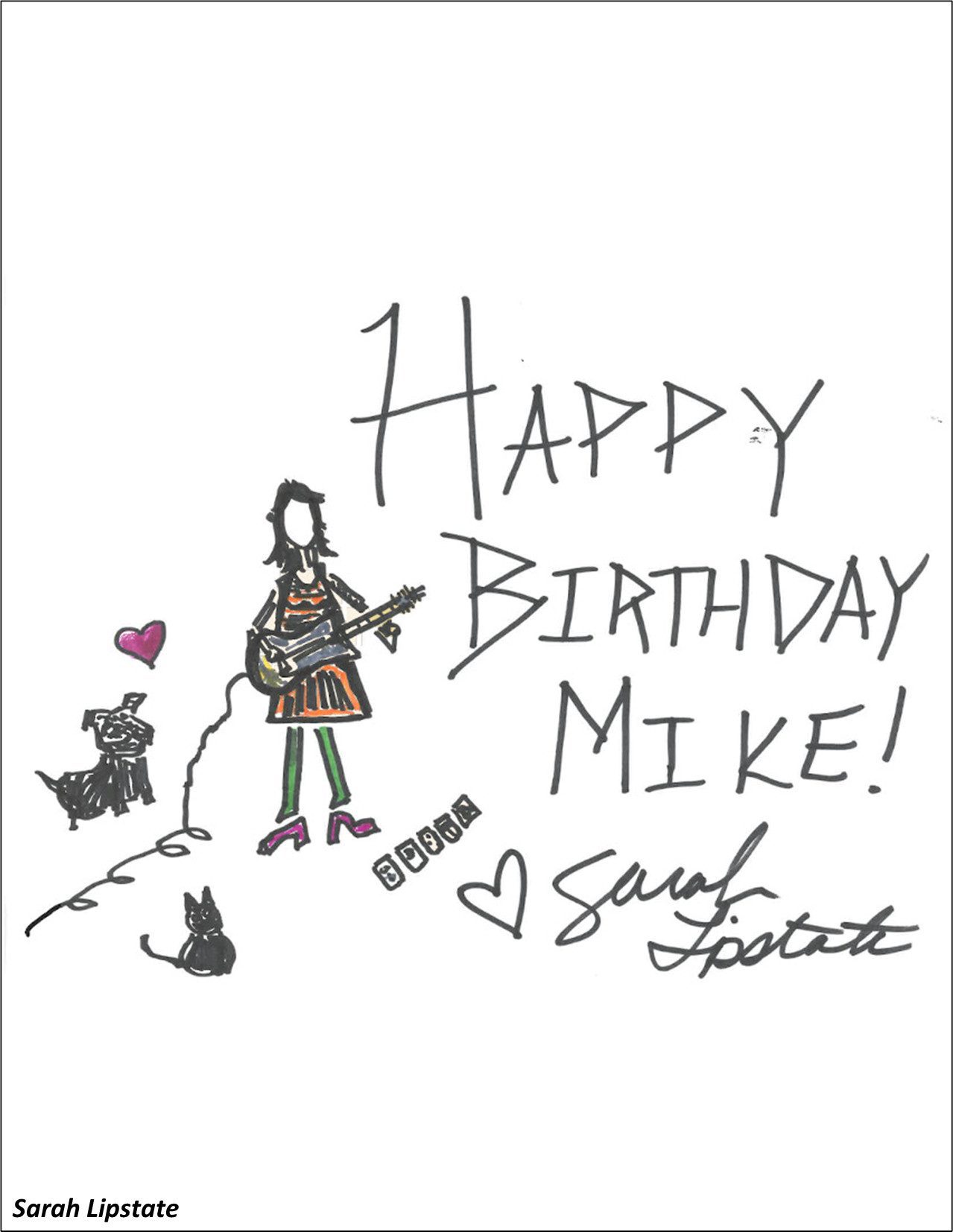

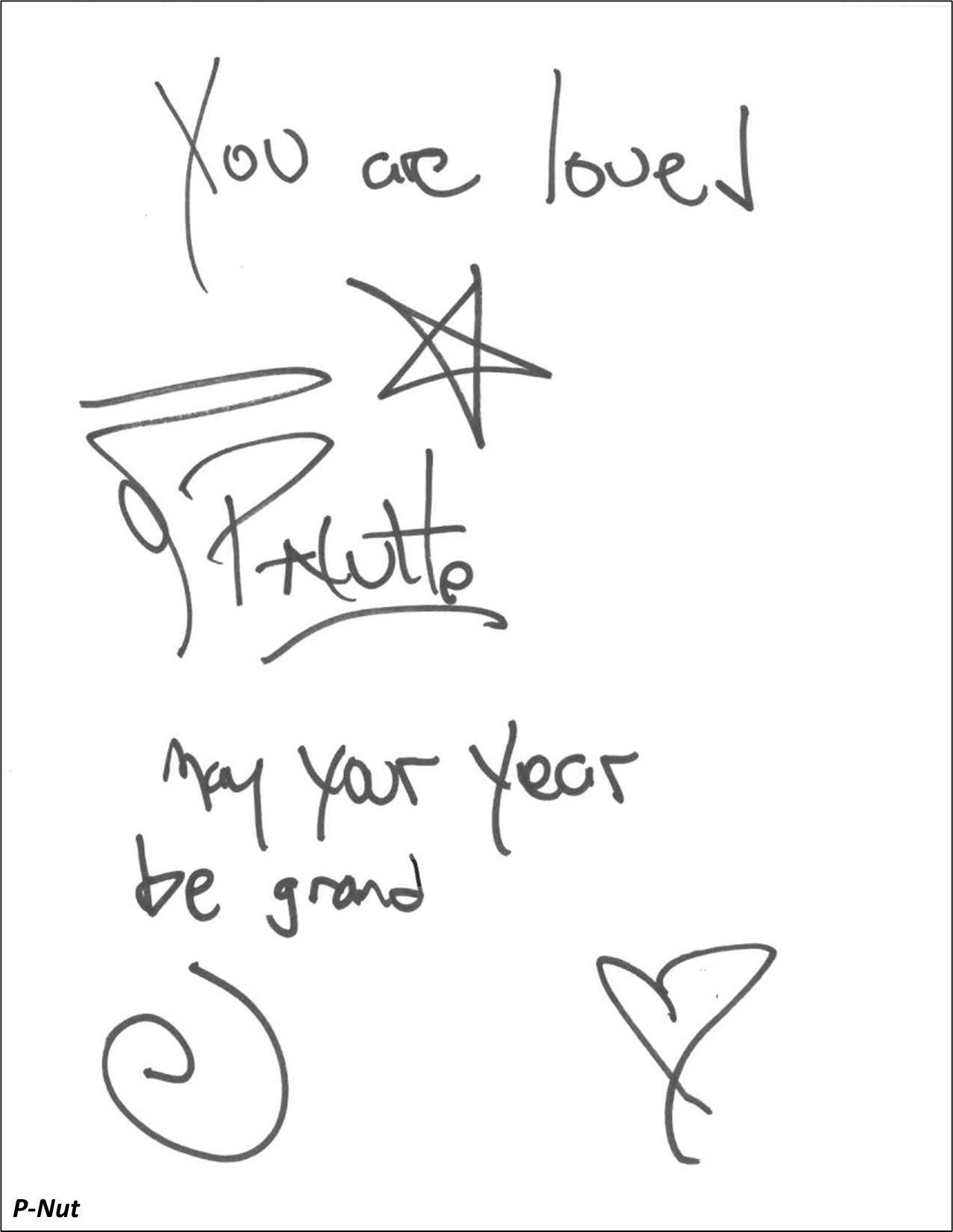

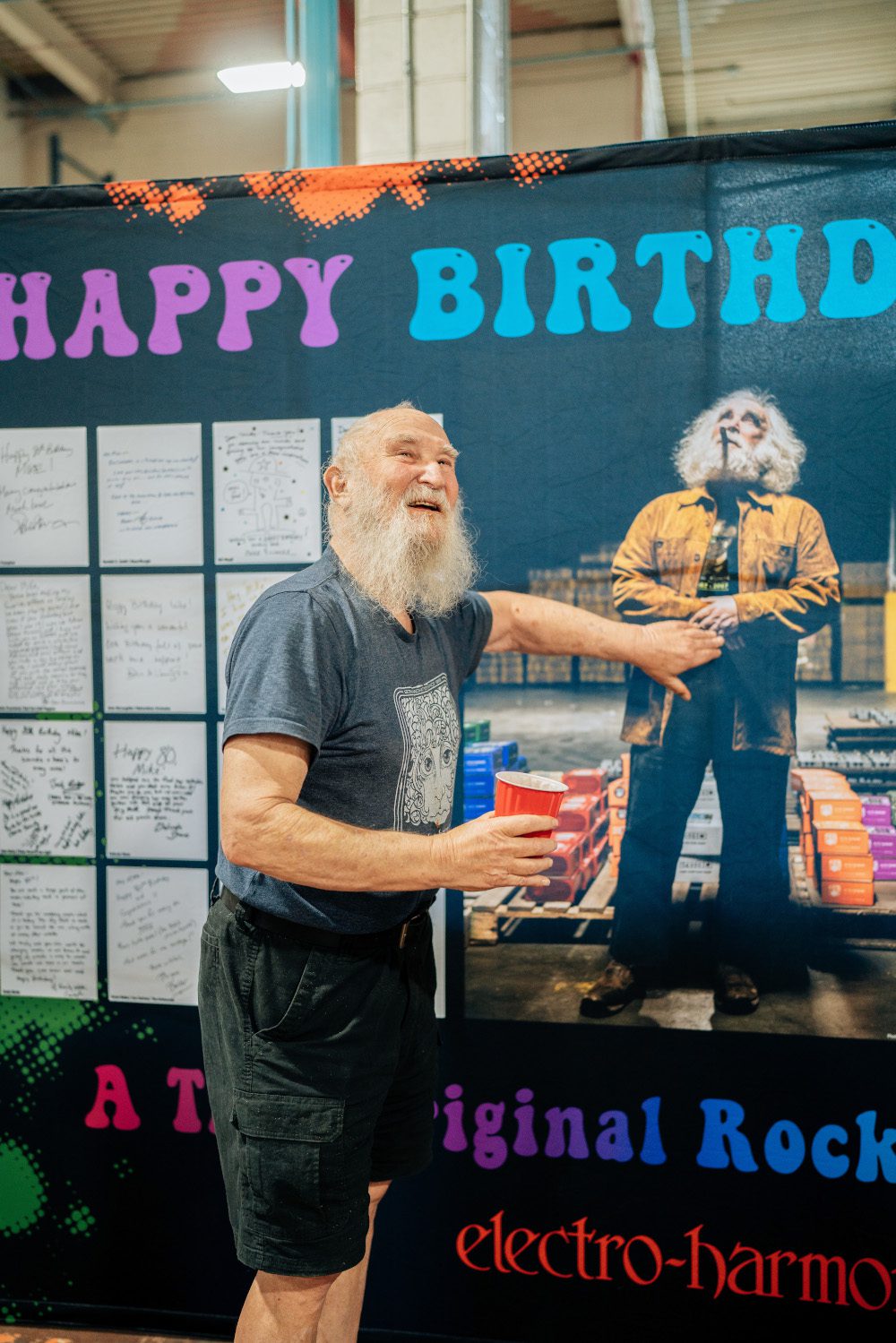

STARS SHINE TO CELEBRATE MIKE MATTHEWS MILESTONE

An array of diverse artists penned personal notes to Mike Matthews wishing the Godfather of Effect Pedals a happy 80th Birthday.

Well-wishers included John Frusciante of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Adrian Belew, the man Frank Zappa said, “reinvented electric guitar,” boundary-breaker Jack White, fabled funkster Bootsy Collins (Mike’s a huge fan of Bootsy’s work with James Brown) and the legendary Peter Frampton.

STARS SHINE TO CELEBRATE MIKE MATTHEWS MILESTONE

EHX PRODUCTS

BIG MUFF PI FUZZ

Of course, the LPB-1 and New York Big Muff are still mainstays of the company’s product line. In addition, because of the incredibly high prices that vintage versions of the Big Muff were commanding on the used market, Mike opted to have his engineers recreate the Triangle, Ram’s Head, Op-Amp and Green Russian Big Muffs. They’ve been received with rave reviews.

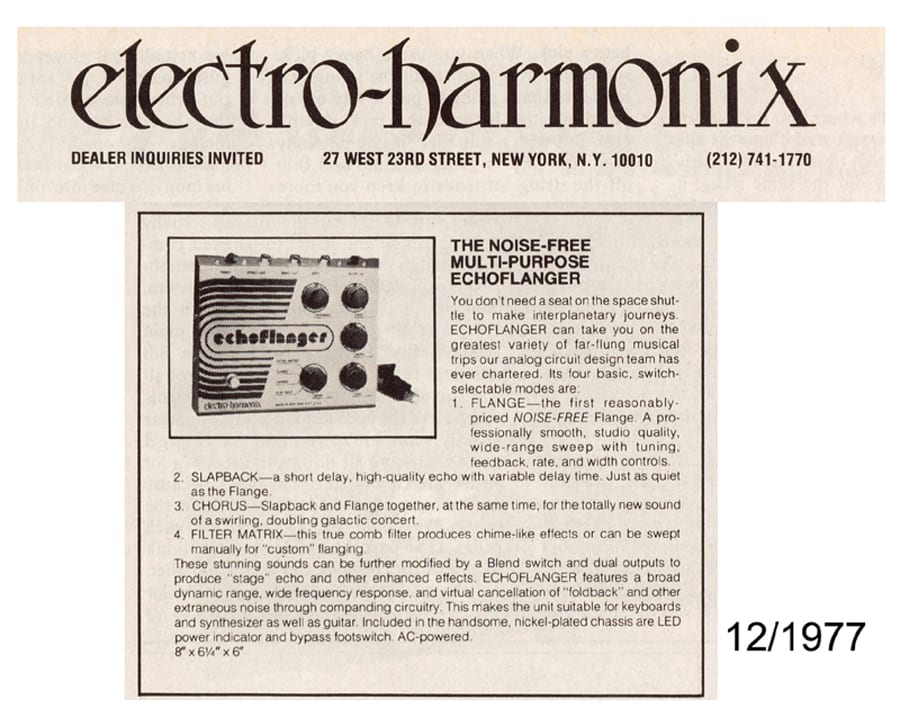

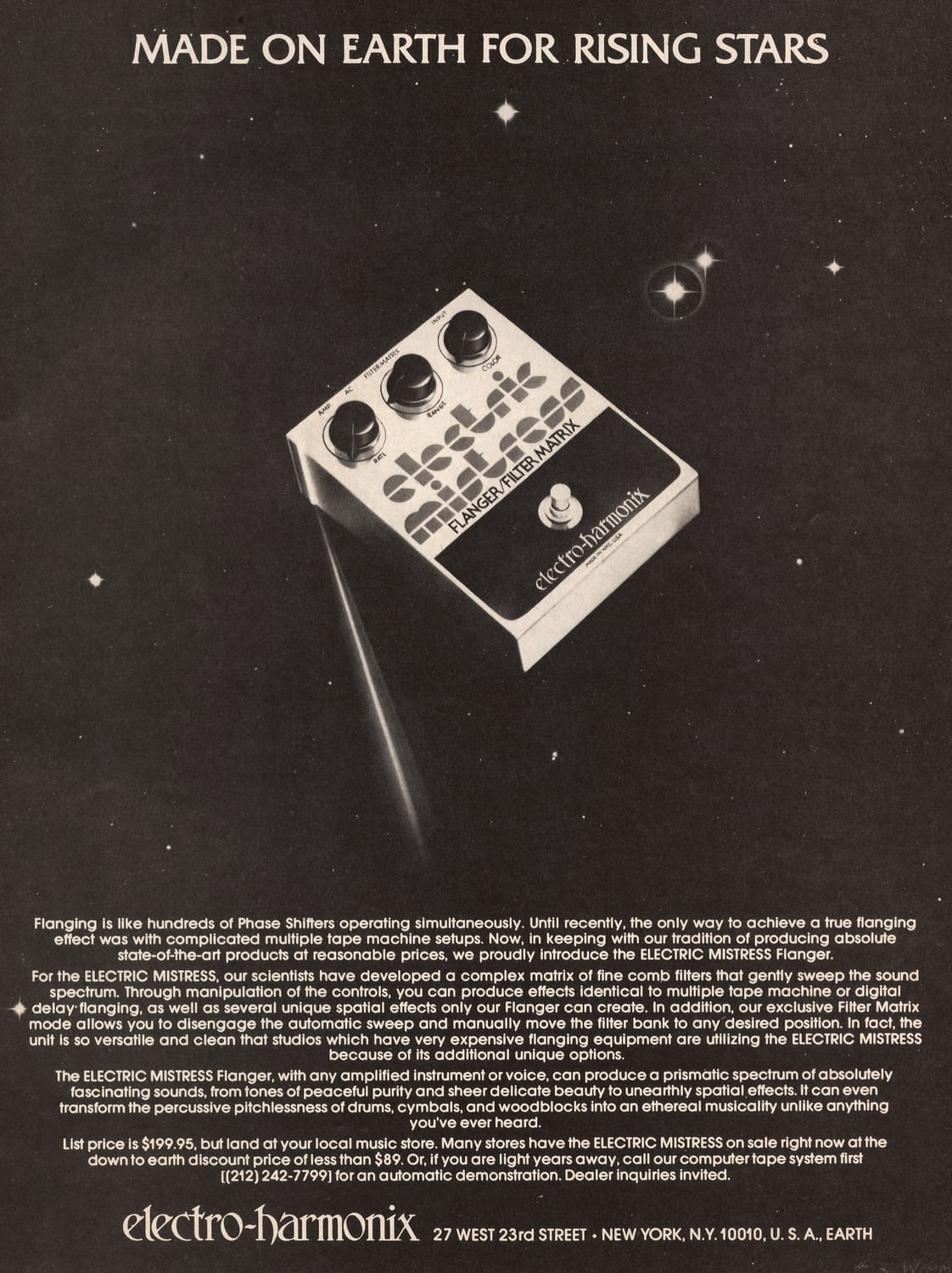

ELECTRIC MISTRESS FLANGER

Innovation has always been at the fore with EHX and is a hallmark of the company. Electro-Harmonix was first with the Electric Mistress Flanger in 1975 and that pedal made it possible for musicians to easily reproduce an effect that was once only possible to create in the recording studio.

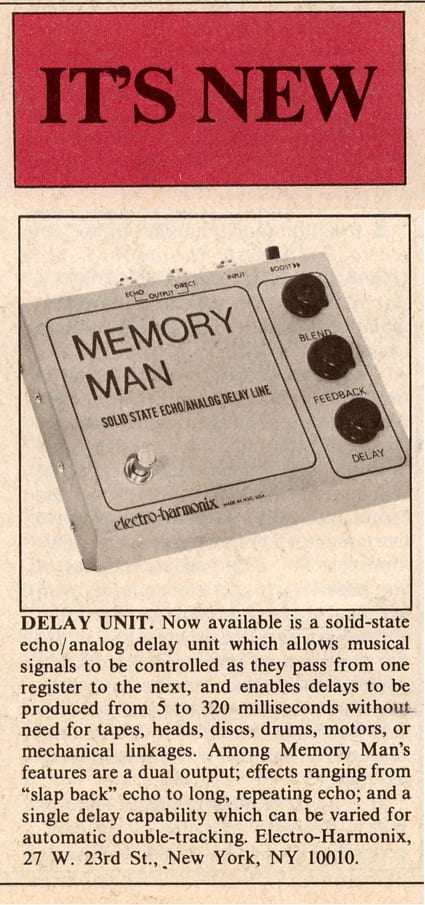

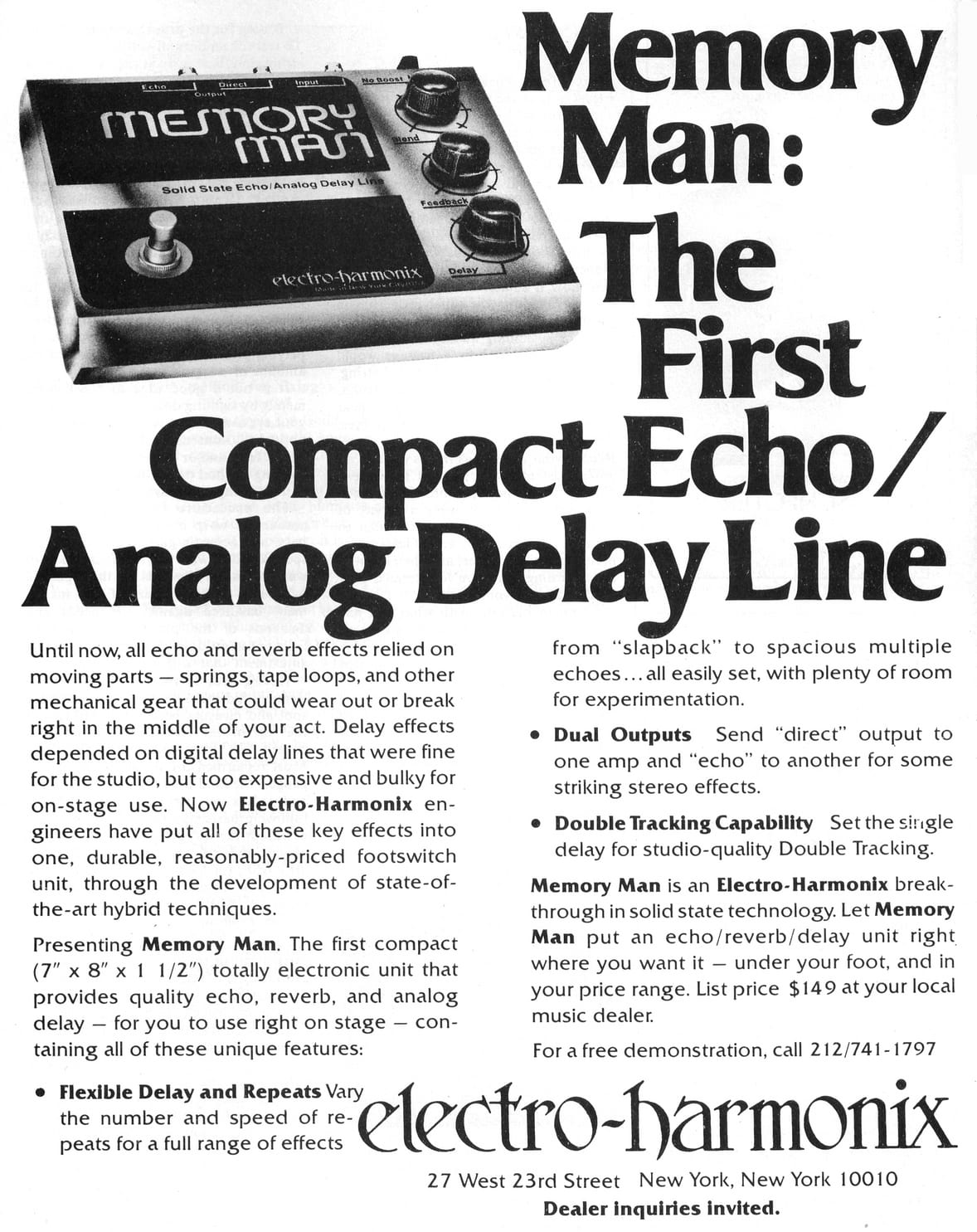

MEMORY MAN DELAY

Another EHX innovation was the analog Memory Man Echo released in 1976. It was the first IC based analog delay that could make discrete echoes! With its lush, organic sound and great convenience over tape delays, it quickly became an instant classic beloved by musicians. Just ask U2’s The Edge about the Deluxe Memory Man!

Nels Cline with his

EHX 16-second Delay

2 SECOND AND 16 SECOND

DELAY & LOOPER

EHX lead the way in looping! The 2 Second Delay was unveiled in 1981. It was the first digital delay pedal and included an Infinite footswitch to allow you to loop whatever was in the delay line at the time the footswitch was depressed.

The 16 Second Delay followed in 1983 and is still beloved by players like Nels Cline. It’s a digital delay with an Infinite function, but it also provides the ability create loops that are a predefined number of beats in length. Plus, it allows you to change the tempo of the beats. This predefined beat length functionality was unique and the 16 Second was the first to do this!

POG & HOG

There are also many EHX originals that are so innovative, competitors have been unable to copy them! For example, in 2005 the POG was released; POG being an acronym for Polyphonic Octave Generator. The HOG, Harmonix Octave Generator, followed in 2009. It provides complete control over ten totally polyphonic voices ranging from two octaves below to four above their guitar’s pitch!

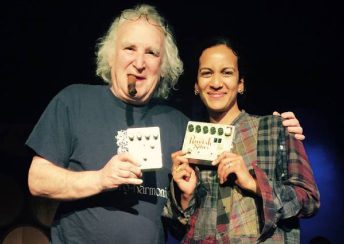

RAVISH SITAR

Mike Matthews with

Anoushka Shankar

The Ravish Sitar pedal took the world by storm in 2011 and transforms an electric guitar into a sitar. The demo video features a cameo performance by Mike Matthews that is a must see.

RAVISH SITAR

The Ravish Sitar pedal took the world by storm in 2011 and transforms an electric guitar into a sitar. The demo video features a cameo performance by Mike Matthews that is a must see.

9 SERIES: MEL9, SYNTH9, C9, KEY9, B9 & BASS9

In 2014, EHX turned the pedal world upside down by introducing the first 9 Series pedal, the B9 Organ Machine. The number 9 is synonymous with the number of presets the pedal provides. Quite easily the most unique pedals in our product line, Electro-Harmonix 9 Series pedals were designed to make your guitar sound like anything but a guitar.

What has proven to be one of the most coveted and beloved members of the 9 Series was introduced in 2016… that was the MEL9 Tape Replay Machine. The Mel9 pays homage to nine of the coolest Mellotron®sounds: Orchestra, Cello, Strings, Flute, Clarinet, Saxophone, Brass, Low Choir and High Choir. And, like all members of the 9 Series, it does it without MIDI, special pickups or any guitar mods.

The SYNTH9 hit the world in 2017 with nine presets that let guitarists emulate the hippest vintage synthesizer sounds ever. Soaring synth leads… funky synth basses… atmospheric synth pads… they’re all possible with the SYNTH9!

The C9 Organ Machine came out in 2014 and leap-frogged off the B9 to give guitarists nine more definitive organ and classic electronic keyboard sounds.

The hits just keep coming and lovers of those unmistakable Rhodes and Wurlitzer sounds got their dreams fulfilled with the unveiling of the KEY9 Electric Piano Machine in 2015. “Riders on the Storm?” “What’d I Say?” The KEY9’s got you covered and as Mike Matthews says: “You’ll dig the way the KEY9 turns you into a Rhodes Scholar!”

The B9 Organ Machine was the first pedal to transform the tone of a guitar or keyboard into that of a convincing full body, electric organ. The B9 emulates some of the most popular and classic electric organ tones with enough tonewheel and combo organ inspiration to light your fire and cook up some green onions!

The BASS9 was unveiled in 2019. It transforms a guitar into nine different basses… and not just any basses! The BASS9 is packed with presets like PRECISION which pays homage to the iconic Fender P Bass®, LONGHORN, which emulates the Danelectro® 6-string bass and is incredible for baritone type tones, SYNTH, a tribute to the classic Taurus® Synthesizer, plus six more.

Be assured that EHX’s legacy of innovation and leadership is still very active and very much alive. There are incredible products in development and on the horizon that will continue to provide musicians with the tools to create without constraints and to explore sounds outside of conventional boundaries!

INTERVIEWS

WITH MIKE

Crain’s New York Stories

See how an entrepreneuring kid from the Bronx grew to become the Godfather of Guitar Effects Pedals.

2006

NAMM Oral History

Mike Matthews has incredible stories to tell! In 2006, NAMM recognized Mike as a spokesperson for his generation of music makers who want to be successful in business while having enough time to rock and roll!

2012

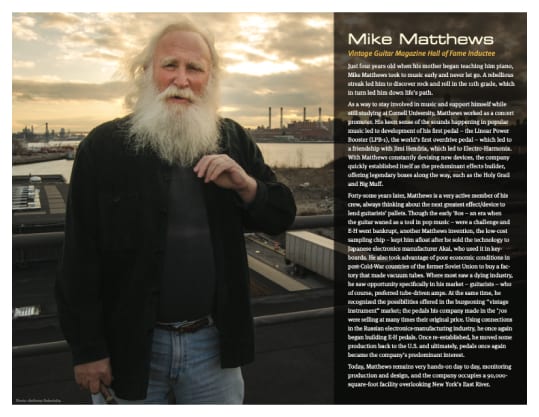

Vintage Guitar Hall of Fame

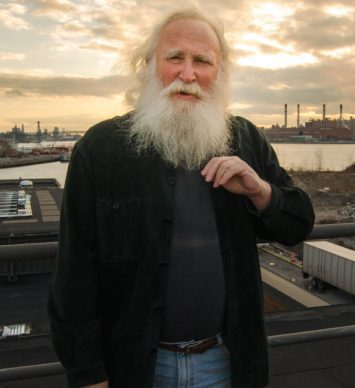

As someone largely considered the Godfather of Effects Pedals, Mike’s position in the music equipment industry is one occupied by a scant few and includes the likes of Leo Fender and Jim Marshall. These are men whose names are synonymous with a particular musical product type and whose legacy is inextricably intertwined with their companies. It was therefore quite a fitting and well-deserved honor when, in January 2013, Mike was inducted into the 2012 Vintage Guitar Hall of Fame joining the ranks of such luminaries as Les Paul, Lloyd Loar and Leo Fender.

2014

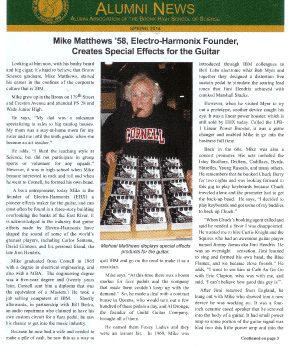

BRONX HIGH SCHOOL OF

SCIENCE NEWSLETTER

The accolades for Mike and Electro-Harmonix have been many. In March 2014, Mike, who is a Bronx native, was feted in the Alumni Association of the Bronx High School of Science newsletter.

2014

BRONX HIGH SCHOOL OF

SCIENCE NEWSLETTER

The accolades for Mike and Electro-Harmonix have been many. In March 2014, Mike, who is a Bronx native, was feted in the Alumni Association of the Bronx High School of Science newsletter.

2014

FORBES FEATURE

2014

FORBES FEATURE

Later that year, Forbes, the global media company known for its focus on business, investing, technology and entrepreneurship interviewed Mike and toured Electro-Harmonix.

Click image to watch video.

2017

MUSIC RADAR INTERVIEW

Music Radar, the global website that dishes on all things music related, met with Mike in November 2017 to, as they said: “Talk about effects units old and new with Electro-Harmonix’s charismatic founder.”

2017

MUSIC TRADES FEATURE

Music Trades magazine published a feature article on Mike in December 2017 dubbed” Rock ‘n’ Roller, Serious About Business” where they explored the fruits of his entrepreneurial spirit throughout Electro-Harmonix’s history.

2018

MANUFACTURING LEGEND!

2018

MANUFACTURING LEGEND!

To commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Electro-Harmonix brand, Guitar Player magazine’s editor-in-chief, Michael Molenda, interviewed Mike Matthews in February 2018. Six years earlier Mike had been inducted into the Guitar Player Hall of Fame as a “Manufacturing Legend!” Mike ended the Guitar Player interview with the following words of wisdom that sum up his career: “If you want to be successful, you have to love what you do, because you’re going to be competing with other people who love what they do, as well.”

If you want to be successful, you have to love what you do, because you’re going to be competeing with other people who love what they do as well.

2018

MUSIC & SOUND RETAILER INTERVIEW

In March 2018, The Music & Sound Retailer magazine’s editor, Brian Berk, spoke with Mike Matthews about a variety of interesting subjects. In the resulting article titled “One of MI’s Greatest Storytellers,” Mike expounded on everything from hanging out with Jimmy James, who later achieved superstardom as Jimi Hendrix, to his views on competition in the pedal marketplace.

2019

HEAPS MAGAZINE ARTICLE

In 2019 Heaps Magazine , self-described as “a Japanese media outlet that explores cultures around the world,” sent a team to New York City to meet Mike Matthews and tour the EHX factory. They published an extensive article in November 2019.

2020

ALMA MATAR HONORS

In January 2020 Cornell’s Alumni Magazine caught up with Mike to find out what the Cornell alumnus had been up to. The resulting article is entitled: “Sound Mind. For decades, Mike Matthews ’62, BEE ’65, MBA ’66, and his company have equipped rock superstars like Pink Floyd and Aerosmith.”

TODAY

THE LEGEND CONTINUES

Mike Matthews’ story, and how it’s totally intertwined with the saga of Electro-Harmonix, are still going strong. As it continues to unfold, we’ll be reporting on it right here!